Do you know that apart from normal postures or posturing, we also have postures that are abnormal like the decorticate posture or decerebrate posture?

This article reviews the assessment and management of decorticate and decerebrate posturing and highlights the role of medical professionals in evaluating and treating patients with these conditions – abnormal postures.

In this post, we will identify the physical exam findings associated with decorticate and decerebrate posturing, describe the pathophysiology of decorticate and decerebrate posturing, outline the prognosis of patients with decorticate and decerebrate posturing and review the etiology of decorticate and decerebrate posturing.

Keep reading.

Before We Proceed, What Do You Understand by Abnormal Posturing? – Abnormal Postures, What Are They?

Abnormal posturing is an involuntary flexion or extension of the arms and legs, indicating severe brain injury. It occurs when one set of muscles becomes incapacitated while the opposing set is not, and an external stimulus such as pain causes the working set of muscles to contract.

The posturing may also occur without a stimulus. Since posturing is an important indicator of the amount of damage that has occurred to the brain, it is used by medical professionals to measure the severity of a coma with the Glasgow Coma Scale (for adults) and the Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale (for infants).

The presence of abnormal posturing indicates a severe medical emergency requiring immediate medical attention. Decerebrate and decorticate posturing are strongly associated with poor outcomes in a variety of conditions.

For example, near-drowning patients that display decerebrate or decorticate posturing have worse outcomes than those that do not. Changes in the condition of the patient may cause alternation between different types of posturing.

Types of Abnormal Postures

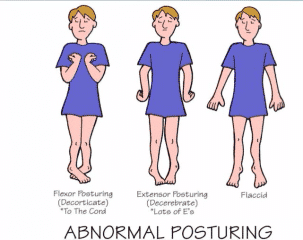

Three types of abnormal posturing are decorticate posturing, with the arms flexed over the chest; decerebrate posturing, with the arms extended at the sides; and opisthotonus, in which the head and back are arched backward.

Decorticate Posture

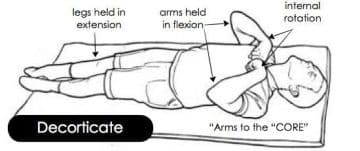

Decorticate posturing, with elbows, wrists, and fingers flexed, and legs extended and rotated inward. Decorticate posturing is also called decorticate response, decorticate rigidity, flexor posturing, or, colloquially, "mummy baby". Patients with decorticate posturing present with the arms flexed or bent inward on the chest, the hands clenched into fists, and the legs extended and feet turned inward.

A person displaying decorticate posturing in response to pain gets a score of three in the motor section of the Glasgow Coma Scale, caused by the flexion of muscles due to the neuro-muscular response to the trauma.

There are two parts to decorticate posturing. The first is the disinhibition of the red nucleus with the facilitation of the rubrospinal tract. The rubrospinal tract facilitates motor neurons in the cervical spinal cord supplying the flexor muscles of the upper extremities.

The rubrospinal tract and medullary reticulospinal tract biased flexion outweigh the medial and lateral vestibulospinal and pontine reticulospinal tract biased extension in the upper extremities.

The second component of decorticate posturing is the disruption of the lateral corticospinal tract which facilitates motor neurons in the lower spinal cord supplying flexor muscles of the lower extremities.

Since the corticospinal tract is interrupted, the pontine reticulospinal and the medial and lateral vestibulospinal biased extension tracts greatly overwhelm the medullary reticulospinal biased flexion tract.

The effects on these two tracts (corticospinal and rubrospinal) by lesions above the red nucleus are what leads to the characteristic flexion posturing of the upper extremities and extensor posturing of the lower extremities.

Decorticate posturing indicates that there may be damage to areas including the cerebral hemispheres, the internal capsule, and the thalamus. It may also indicate damage to the midbrain.

While decorticate posturing is still an ominous sign of severe brain damage, decerebrate posturing is usually indicative of more severe damage at the rubrospinal tract, and hence, the red nucleus is also involved, indicating a lesion lower in the brainstem.

Decerebrate Posture

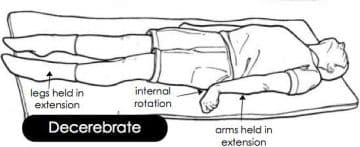

Decerebrate rigidity or abnormal extensor posturing; Decerebrate posturing is also called a decerebrate response, decerebrate rigidity, or extensor posturing. It describes the involuntary extension of the upper extremities in response to external stimuli. In decerebrate posturing, the head is arched back, the arms are extended by the sides, and the legs are extended.

A hallmark of decerebrate posturing is extended elbows. The arms and legs are extended and rotated internally. The patient is rigid, with the teeth clenched. The signs can be present on only one side of the body or on both sides, and they may be present just in the arms, or they may be intermittent.

A person displaying decerebrate posturing in response to pain receives a score of two in the motor section of the Glasgow Coma Scale (for adults) and the Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale (for infants), due to the muscles extending because of the neuro-muscular response to the trauma.

Decerebrate posturing indicates brain stem damage, specifically damage below the level of the red nucleus (e.g., mid-collicular lesion). It is exhibited by people with lesions or compression in the midbrain and lesions in the cerebellum.

Decerebrate posturing is commonly seen in pontine strokes. A patient with decorticate posturing may begin to show decerebrate posturing or may go from one form of posturing to the other. Progression from decorticate posturing to decerebrate posturing is often indicative of uncal (transtentorial) or tonsillar brain herniation.

Activation of gamma motor neurons is thought to be important in decerebrate rigidity due to studies in animals showing that dorsal-root transection eliminates decerebrate rigidity symptoms. Transection releases the centers below the site from higher inhibitory controls.

In competitive contact sports, abnormal posturing (typically of the forearms) can occur with an impact to the head and is termed the fencing response. In this case, the temporary posturing display indicates transient disruption of brain neurochemicals, which wanes within seconds.

Causes of Abnormal Posturing

Abnormal posturing can be caused by conditions that lead to large increases in intracranial pressure. Such conditions include traumatic brain injury, stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, brain tumors, brain abscesses, and encephalopathy.

Abnormal posturing due to stroke usually only occurs on one side of the body and may also be referred to as spastic hemiplegia. Diseases such as malaria are also known to cause the brain to swell and cause this posturing effect.

Decerebrate and decorticate posturing can indicate that brain herniation is occurring or is about to occur. Brain herniation is an extremely dangerous condition in which parts of the brain are pushed past hard structures within the skull. In herniation syndrome, which is indicative of brain herniation, decorticate posturing occurs, and, if the condition is left untreated, develops into decerebrate posturing.

Abnormal posturing has also been displayed by patients with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, diffuse cerebral hypoxia, and brain abscesses.

It has also been observed in cases of judicial hanging, although strapping of the arms and legs may hide the effect.

Children

In children younger than age two, posturing is not a reliable finding because their nervous systems are not yet developed. However, Reye's syndrome and traumatic brain injury can both cause decorticate posturing in children.

For reasons that are poorly understood, but which may be related to high intracranial pressure, children with malaria frequently exhibit decorticate, decerebrate, and opisthotonic posturing.

Prognosis

Normally people displaying decerebrate or decorticate posturing are in a coma and have a poor prognosis, with risks for cardiac arrhythmia or arrest and respiratory failure.

Decorticate Vs Decerebrate Posturing – Introducing How Both Work in Relation to Each Other

Decorticate and decerebrate posturing are both considered pathological posturing responses to usually noxious stimuli from an external or internal source. Both involve stereotypical movements of the trunk and extremities and are typically indicative of significant brain or spinal injury. The Nobel Laurette Charles Sherrington first described decerebrate posturing in 1898 after transecting the brainstems of live monkeys and cats.

Synonymous terms for decorticate posturing include abnormal flexion, decorticate rigidity, flexor posturing, or decorticate response. Synonymous terms for decerebrate posturing include abnormal extension, decerebrate rigidity, extensor posturing, or decerebrate response.

There is a criticism within the literature of the use of the terms decorticate and decerebrate posturing in clinical contexts due to their association with discrete anatomical locations that, in reality, may not be so prescriptive. Brain lesions of several anatomical regions may cause both postures, though they do usually involve some degree of brainstem injury.

It is, however, accepted that decorticate typically requires an injury more rostral than decerebrate posturing. In most literature, this level is considered the red nucleus at the intercollicular level of the midbrain.

Watch the video below to know more about these abnormal postures:

Decorticate Vs. Decerebrate Posturing – The Difference

Decorticate Posturing

Decorticate posturing is described as abnormal flexion of the arms with the extension of the legs. Specifically, it involves slow flexion of the elbow, wrist, and fingers with adduction and internal rotation at the shoulder.

The lower limbs show extension and internal rotation at the hip, with the extension of the knee and plantar flexion of the feet. Toes are typically abducted and hyperextended.

Decorticate posture is an abnormal posturing in which a person is stiff with bent arms, clenched fists, and legs held out straight. The arms are bent in toward the body and the wrists and fingers are bent and held on the chest.

This type of posturing is a sign of severe damage to the brain. People who have this condition should get medical attention right away. Decorticate posture is a sign of damage to the nerve pathway in the midbrain, which is between the brain and the spinal cord.

The midbrain controls motor movement. Although decorticate posture is serious, it is usually not as serious as a type of abnormal posture called decerebrate posture. The posturing may occur on one or both sides of the body.

Decerebrate Posturing

Decerebrate posturing is described as adduction and internal rotation of the shoulder, extension at the elbows with pronation of the forearm, and flexion of the fingers.

As with decorticate posturing, the lower limbs show extension and internal rotation at the hip, with the extension of the knee and plantar flexion of the feet. Toes are typically abducted and hyperextended.

Teasdale and Jennett advocated not using the term 'decerebrate' in the assessment of coma due to its association with a specific physio-anatomical correlation, but rather using the term 'extension.'

The Etiology and Cause of Decorticate and Decerebrate Posturing

There are numerous causes of abnormal posturing including supratentorial and infratentorial lesions, alongside more diffuse pathologies such as metabolic and infective causes:

Supratentorial Lesions

- Abscess

- Extra-axial hematoma: subdural and extradural

- Hydrocephalus

- Intracerebral hemorrhage

- Raised intracranial pressure

- Traumatic brain injury including diffuse axonal injury

- Tumor

Infratentorial Lesion

- Abscess

- Hydrocephalus

- Infarct: brainstem or bilateral diencephalic

- Intracerebral hemorrhage: cerebellar or brainstem

- Traumatic brain injury including diffuse axonal injury

- Tumor

Diffuse and Metabolic

- Cerebral malaria

- Electrolyte abnormalities: hyponatremia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia

- Encephalitis

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Hypoxic brain injury

- Hypoglycemia

- Lead poisoning

- Meningitis

- Reye syndrome

Other causes include:

- Stroke

- Brain problems due to drugs, poisoning, or infection

- Brain problem due to liver failure

- Infection

- Brain injury from lack of oxygen

In patients with preexisting structural lesions of the central nervous system, episodes of decerebrate posturing can occur in response to numerous physiological factors including, but not exclusive to, fever, hypoxia; metabolic disturbance; sensory irritation; hypoglycemia; and meningeal irritation.

The Epidemiology of Decorticate and Decerebrate Posturing

Data on the incidence of abnormal posturing is not published. However, the incidence of pathologies that commonly cause decorticate and decerebrate posturing is available.

The commonest cause of decorticate and decerebrate posturing is traumatic brain injury (TBI). A 2019 systematic review estimates there to be 69 million TBI worldwide each year, with 7.95% being classed as severe. Severe TBI is defined as patients with a GCS of 8 or fewer.

The Pathophysiology of Decorticate and Decerebrate Posturing

Typically, the anatomical divide associated with decorticate and decerebrate posturing is the intercollicular line at the level of the red nucleus. However, this concept has been criticized as lesions in the supratentorial region can also cause both decorticate and decerebrate posturing, though the brainstem is typically involved.

Both posturing types are stereotypical; however, they can be present in varying degrees and even asymmetrically with decorticate on one side and decerebrate contralaterally. An inconsistent presentation of a given posture tends to suggest a lesser degree of injury.

Decerebrate Posturing

Decerebrate posturing has been demonstrated in monkeys with a transecting lesion at the level between the superior and inferior colliculi within the midbrain. This is also described as being at or below the level of the red nucleus. Sherrington performed live animal studies where anesthetized monkeys had their cerebral cortex removed from the intercollicular level upwards.

The animals continued to breathe independently and developed stereotypical extension rigidity of the extremities. A study with intercollicular transection showed that extensor posturing only occurred in the context of either noxious stimuli, passive hyperextension of the head, or metabolic disturbance such as hypoxia.

Decerebrate posturing can be seen in patients with large bilateral forebrain lesions with progression caudally into the diencephalon and midbrain. It can also be caused by a posterior fossa lesion compressing the midbrain or rostral pons.

Though decerebrate posturing implies a destructive structural lesion, it can also be caused by reversible metabolic disturbances such as hypoglycemia and hepatic encephalopathy.

Through animal models and human studies, it has been shown that the vestibulospinal tract plays a major role in decerebrate posturing. The vestibulospinal pathways have an excitatory effect on extensor motor neurons in the spine while inhibiting the flexor motor neurons.

The vestibular nuclei receive input from the vestibular apparatus and spinal somatosensory pathways while receiving modulatory signals from the cerebral cortex and the fastigial nucleus of the cerebellum.

In isolation, the vestibular nucleus, via the vestibulospinal tract, causes activation of extensor motor neurons in the spinal cord and inhibition of flexor motor neurons. However, under normal physiology, the higher brain centers of the cortex and cerebellum inhibit the vestibular nuclei, thus preventing this reflex.

Decerebrate posturing results from a disconnection between the modulatory higher centers and the vestibular nuclei, resulting in unsuppressed extensor posturing.

Decorticate Posturing

The mechanism for decorticate posturing is not as well studied as that of decerebrate. Phylogenetically, the region of the red nucleus within the midbrain plays a significant part in locomotion. In primates, the rubrospinal tract influences primitive grasp reflexes, particularly in infants, and is, incidentally, responsible for crawling.

The rubrospinal tract carries signals from the red nucleus to the spinal motor neurons. Primates are reliant on fine motor skills, and therefore the motor cortex via the corticospinal tracts is more prominent in movement than phylogenetically lower regions.

Extensive lesions involving the forebrain, diencephalon, or rostral midbrain are known to cause decorticate posturing. This includes the motor cortex, premotor cortex, corona radiata, internal capsule, and thalamus.

In primates, the rubrospinal tract descends as far as the thoracic spine; it, therefore, has effects on the upper limbs but not the lower limbs. The red nucleus, via the rubrospinal tract, causes a flexion, grasping-type reflex of the upper limbs.

The higher brain centers, such as the cerebral cortex, inhibit this reflex during normal physiology. With a lesion of the corticospinal tract, the red nucleus is disinhibited, and the flexion reflex of the upper limbs is unimpeded.

The vestibulospinal tracts, as discussed above, are also left disinhibited, and extension of the lower limbs occurs. This flexion of the upper limbs and extension of lower limbs is decorticate posturing.

The red nucleus is anatomically at the intercollicular level, and thus lesions above the red nucleus tend to cause decortication and lesions below, decerebration. As compression advances from the regions of the forebrain and diencephalon to the brainstem, abnormal posturing can progress from decorticate to decerebrate.

The Differential Diagnosis of Decorticate and Decerebrate Posturing

Normal flexion, also known as withdrawal to pain, can appear similar to decorticate posturing. However, normal flexion is a rapid and variable movement compared with the slow and stereotypical movements of abnormal flexion.

In normal flexion, the shoulder abducts away from the body, the wrist is either neutral or extended and importantly, there is no extension in the lower limbs. In abnormal flexion, the shoulder adducts, and internal rotates, and the wrist flexes with forearm pronation. A key feature is the extension of the lower limbs.

Spinal reflexes may still be present following brain death. One study found motor spinal responses present in 22% of patients with confirmed brain death. These can be mistaken for abnormal posturing movements such as decerebration.

Opisthotonus is extrapyramidal abnormal posturing seen in cerebral palsy, tetanus, drowning victims, TBI, and poisoning. It is abnormal posturing with a dramatically arched back and neck. Paratonia, or gegenhalten, can also look like abnormal posturing and is typically caused by encephalopathy or neurodegenerative conditions.

Lastly, patients with corticospinal tract injuries, such as ischemic strokes, hemorrhages, or tumors, can develop spasticity.

Usually, in the upper limb flexor muscles dominate, and extensors in the lower limb, similar to decorticate posturing. The most striking difference between spasticity and abnormal posturing is the preservation of consciousness in spastic patients.

Management/Treatment of Decorticate and Decerebrate Posturing

Treatment is directed at the underlying cause, for instance, correcting, where possible, metabolic derangements, and treating infections. In TBI, evacuation of extra-axial hematoma can improve survival. Some pathologies may not be reversible, such as hypoxic brain injury, and thus supportive approaches are taken.

When to Contact a doctor

Abnormal posturing of any kind usually occurs with a reduced level of alertness. Anyone who has an abnormal posture should be examined right away by a healthcare provider and treated right away in a hospital.

What to Expect at Your Hospital or Clinic Visit

The person will receive emergency treatment. This includes getting a breathing tube and breathing assistance. The person will likely be admitted to the hospital and placed in the intensive care unit.

After the condition is stable, the provider will get a medical history from family members or friends and a more detailed physical examination will be done. This will include a careful examination of the brain and nervous system.

Medical history questions may include:

- When did the symptoms start?

- Is there a pattern to the episodes?

- Is the body posture always the same?

- Is there any history of a head injury or drug use?

- What other symptoms occurred before or with the abnormal posturing?

Tests that may be done include:

- Blood and urine tests to check blood counts, screen for drugs and toxic substances, and measure body chemicals and minerals

- Cerebral angiography (a dye and x-ray study of blood vessels in the brain)

- MRI or CT scan of the head

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) (brain wave testing)

- Intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring

- Lumbar puncture to collect cerebrospinal fluid

The outlook depends on the cause. There may be brain and nervous system injury and permanent brain damage, which can lead to:

- Coma

- Inability to communicate

- Paralysis

- Seizures

The Complications of Decorticate and Decerebrate Posturing

As will be discussed in the prognosis section below, complications include death and poor functional neurological outcome. In the immediate period, patients in a coma can also have problems maintaining their airways and controlling their cardiorespiratory system.

The Prognosis of Decorticate and Decerebrate Posturing

Abnormal posturing is an ominous sign, with only 37% of decorticate patients surviving following head injury and only 10% in decerebrate. Overall, children requiring admission to the hospital due to head injury have a mortality of 10% to 13%; however, in severe cases with decerebrate posturing, the mortality is 71%.

Other studies have shown similar mortality rates of 68% to 83% in TBI with decerebrate posturing. Factors that favored survival in TBI with decerebrate posturing included younger patients’ age, admission within 6 hours of injury, and extradural hematoma. Poorer outcomes were found in acute subdural hematoma and older age.

Outcomes in patients with abnormal posturing following hypoxic brain injury were reviewed in 210 patients. Abnormal posturing, or GCS motor score of less than 4, after one-day post-insult, suggested virtually no chance of regaining independence.

Patients with gunshot wounds to the head who demonstrated either decorticate or decerebrate posturing had a close to zero chance of a meaningful recovery. The Hunt and Hess subarachnoid hemorrhage severity grading scale includes decerebrate posturing in grades 4 and 5. They quoted 42% and 77% mortality, respectively.

The Evaluation

Decorticate and decerebrate posturing are clinical diagnoses and should be considered a pathological sign of a neurological injury rather than a diagnosis unto themselves.

Due to the variety of etiologies that can cause these findings, numerous investigations may be appropriate. As discussed above, compressive lesions may benefit from surgical intervention, best done in a timely manner; therefore, early intracranial imaging such as CT or MRI is warranted.

Other causes, such as infection and metabolic disturbance, can be investigated with laboratory tests, including serum and CSF sampling.

Decorticate and decerebrate posturing are medical emergencies. Early diagnosis and intervention may improve survival and functional outcome. Herniation syndromes raised intracranial pressure (ICP), intracranial hemorrhage, TBI, and penetrating trauma may warrant emergent neurosurgical involvement.

Infective and metabolic causes require supportive therapies and the involvement of medical, neurological, or infectious disease specialists. Patients with abnormal posturing likely require aggressive goal-directed therapies, and thus an intensive care environment may be appropriate.

Alongside this, medical therapies to reduce acutely raised intracranial pressure such as mannitol and hypertonic saline have level III evidence. Level II evidence has shown hyperventilation may benefit raised ICP, though only as a temporizing measure and not prophylactically.

That said, given the often poor outcome in patients with abnormal posturing, particularly decerebration, aggressive treatment may be ethically questionable, and a case-by-case assessment is required.