Introduction to Dysautonomia

Dysautonomia refers to a disorder of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) function that generally involves failure of the sympathetic or parasympathetic components of the ANS, but dysautonomia involving excessive or overactive ANS actions also can occur.

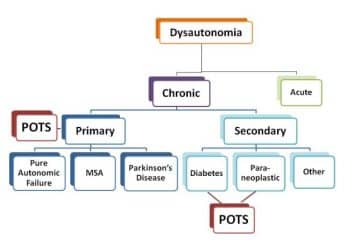

Dysautonomia can be local, as in reflex sympathetic dystrophy, or generalized, as in pure autonomic failure. It can be acute and reversible, as in Guillain-Barre syndrome, or chronic and progressive.Several common conditions such as diabetes and alcoholism can include dysautonomia.

Dysautonomia also can occur as a primary condition or in association with degenerative neurological diseases such as Parkinson's disease. Other diseases with generalized, primary dysautonomia include multiple system atrophy and familial dysautonomia.

Hallmarks of generalized dysautonomia due to sympathetic failure are impotence (in men) and a fall in blood pressure during standing (orthostatic hypotension). Excessive sympathetic activity can present as hypertension or a rapid pulse rate.

Who Might Get Dysautonomia?

Dysautonomia, also called autonomic dysfunction or autonomic neuropathy, is relatively common. Worldwide, it affects more than 70 million people. It can be present at birth or appear gradually or suddenly at any age. Dysautonomia can be mild to serious in severity and even fatal (rarely). It affects women and men equally.

Dysautonomia can occur as its own disorder, without the presence of other diseases. This is called primary dysautonomia. It can also occur as a condition of another disease. This is called secondary dysautonomia.

Examples of diseases in which secondary dysautonomia can occur include:

- Diabetes.

- Parkinson’s disease.

- Muscular sclerosis.

- Rheumatoid arthritis.

- Lupus.

- Sjogren's syndrome.

- Sarcoidosis.

- Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis.

- Celiac disease.

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

- Chiari malformation.

- Amyloidosis.

- Guillain-Barre syndrome.

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

- Lambert-Eaton syndrome.

- Vitamin B and E deficiencies

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- Lyme disease.

Symptoms of Dysautonomia

Dysautonomia can affect ANS functions including:

- Blood pressure.

- Breathing.

- Digestion.

- Heart rate.

- Kidney function.

- Pupil dilation and constriction in the eyes.

- Sexual function.

- Body and skin temperature control.

There are many symptoms of dysautonomia. Symptoms vary from patient to patient. Symptoms can be present some of the time, go away, and return at any time.

Some symptoms may appear at a time of physical or emotional stress or can appear when you are perfectly calm. Some symptoms may be mild in some patients; in others, they may interfere constantly with daily life.

A common sign of dysautonomia is orthostatic intolerance,1ninds gov/ which means you can’t stand up for long, without feeling faint or dizzy. Other signs and symptoms of dysautonomia you may experience include:

- Balance problems

- Noise/light sensitivity

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain/discomfort

- Dizziness

- Lightheadedness

- Vertigo

- Swings in body and skin temperature

- Ongoing tiredness

- Visual disturbances (blurred vision)

- Difficulty swallowing

- Nausea and vomiting,

- GI problems (constipation)

- Fast or slow heart rate

- Heart palpitations

- Brain “fog”

- Forgetfulness

- Large swings in heart rate and blood pressure

- Weakness

- Mood swings

- Fainting

- Loss of consciousness

- Sweat less than normal or not at all

- Sleeping problems

- Migraines or frequent headaches

- Dehydration

- Frequent urination

- Incontinence

- Erectile dysfunction

- Low blood sugar

- Exercise intolerance (heart rate doesn’t adjust to changes in activity level)

Causes of Dysautonomia

Dysautonomia happens when the nerves in your ANS don’t communicate as they should. When your ANS doesn’t send messages or receive messages as it should or the message isn’t clear, you experience a variety of symptoms and medical conditions.

Certain conditions and events can bring on the symptoms of dysautonomia. These triggers or causes of dysautonomia include:

- Alcohol consumption.

- Dehydration.

- Stress.

- Tight clothing.

- Hot environments.

Risk Factors for Dysautonomia

You may be at higher risk for dysautonomia if you:

- Are a Jewish person of Eastern European heritage (only for the familial dysautonomia form of the condition).

- Have diabetes, amyloidosis, certain autoimmune diseases, and other medical conditions mentioned earlier in this article in the question or section; “who might get dysautonomia?”

- Have a family member with the disorder.

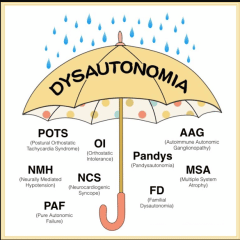

The Different Types of Dysautonomia

Dysautonomia is a medical term for a group of different conditions that share a common problem – improper functioning of the autonomic nervous system. Dysautonomia can either be primary or secondary.

There are at least 15 types of dysautonomia. The most common are neurocardiogenic syncope (NCS) and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).2clevelandclinic

The following are the main types of dysautonomia:

- Neurocardiogenic syncope (NCS):

NCS is the most common form of dysautonomia. It can cause fainting spells that happen once or twice in your lifetime or multiple times every day. NCS is also called situational syncope or vasovagal syncope.

Some people may only experience it occasionally, whereas in others, it will be frequent enough to disrupt their life.

Gravity naturally pulls the blood downward, but a healthy ANS adjusts the heartbeat and muscle tightness to prevent blood from pooling in the legs and feet and to ensure blood flow to the brain.

NCS involves a failure in the mechanisms that control this, and the temporary loss of blood circulation in the brain causes fainting.

For people who faint only occasionally, avoiding known triggers can help. Possible triggers include:

- dehydration

- stress

- alcohol consumption

- very warm environments

Doctors may recommend medication, such as beta-blockers, or the implantation of a pacemaker to treat persistent or severe cases of NCS.

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS):

A disorder that causes problems with circulation (blood flow), POTS can cause your heart to beat too fast when you stand up. It can lead to fainting, chest pain, and shortness of breath.

POTS affects 1–3 million people in the United States, about 80% of whom are female. It often affects people with an autoimmune condition.

The symptoms include:

- lightheadedness and fainting

- tachycardia, which is an abnormally fast heart rate

- chest pain

- shortness of breath

- stomach upset

- shaking

- becoming easily exhausted by exercise

- oversensitivity to temperatures

POTS is normally a secondary dysautonomia. Researchers have found high levels of autoimmune markers in people with the condition. In addition, those with POTS are more likely than the general population to have an autoimmune disorder, such as Sjögren’s disease or lupus.

Apart from autoimmune factors, conditions that doctors link to POTS or POTS-like symptoms include:

- some genetic disorders or abnormalities

- diabetes

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a collagen protein disorder that can lead to joint hypermobility and “stretchy” veins

- infections, such as mononucleosis, Lyme disease, extrapulmonary mycoplasma pneumonia, or hepatitis C

- toxicity from alcohol use disorder, chemotherapy, or heavy metal poisoning

- pregnancy, surgery, or other trauma to the body

- Familial dysautonomia (FD):

People inherit this type of dysautonomia from their genetic relatives. It can cause decreased pain sensitivity, lack of eye tears, and trouble regulating body temperature. FD is more likely to affect Jewish people (Ashkenazi Jewish heritage) of Eastern European heritage and is a very rare type of dysautonomia.

The symptoms, which typically appear in infancy or childhood, include:

feeding difficulties

- slow growth

- the inability to produce tears

- frequent lung infections

- difficulty maintaining body temperature

- prolonged breath-holding

- delayed development, including walking and speech

- bed-wetting

- poor balance

- kidney and heart problems

The condition can lead to a dysautonomic crisis, which involves rapid fluctuations in blood pressure and heart rate, dramatic personality changes, and complete digestive shutdown.

Familial dysautonomia is a serious condition that is usually fatal. There is no cure. However, the incidence of FD is gradually decreasing over time due to prenatal screening and testing.

- Multiple system atrophy (MSA):

A life-threatening form of dysautonomia, multiple system atrophy develops in people over 40 years old. It can lead to heart rate issues, low blood pressure, erectile dysfunction, and loss of bladder control.

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is rare, with experts estimating that it affects 2–5 people in every 100,000. It usually occurs after the age of 40 years. Doctors may mistake it for Parkinson’s disease because the early symptoms of the two conditions are similar.

In the brains of people with MSA, certain regions slowly break down — in particular, the cerebellum, basal ganglia, and brain stem. This leads to motor difficulties, speech issues, balance problems, poor blood pressure, and problems with bladder control.

MSA is not hereditary or contagious, and it is not related to multiple sclerosis. Researchers know little else about what may cause MSA. As a result, there is currently no cure and no specific treatment options.

However, people can manage certain symptoms through lifestyle changes and medications.

Pure autonomic failure:

People with this form of dysautonomia experience a fall in blood pressure upon standing and have symptoms including dizziness, fainting, visual problems, chest pain, and tiredness. Symptoms are sometimes relieved by lying down or sitting.

- Autonomic dysreflexia:

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) can affect people with spinal cord injuries (SCIs). As a result, doctors class it as a secondary dysautonomia. The higher the level of the SCI, the greater the risk of AD. Up to 90% of people with cervical spinal or high thoracic SCIs could develop AD.

AD usually involves the irritation of the region below the level of a person’s injury. A range of conditions and injuries can bring on AD, including urinary tract infections and skeletal fractures.

In AD, the damaged spine prevents pain messages from reaching the brain. The ANS reacts inappropriately, producing severe spikes in blood pressure. The symptoms include:

- headaches

- blotchy skin

- a blocked nose

- a slow pulse

- nausea

- goosebumps and clammy skin near the site of the injury

Most treatments aim to relieve the initial injury or irritation, thereby preventing further attacks of AD.

- Baroreflex failure:

This condition is rare and affects blood pressure.

The baroreflex mechanism is one way in which the body maintains a healthy blood pressure. Baroreceptors are stretch receptors situated in important blood vessels. They detect stretching in the artery walls and send messages to the brain stem.

If these messages fail, blood pressure can become too low when a person is resting, or it can rise dangerously high during times of stress or activity.

Other possible symptoms include headaches, excessive sweating, and an abnormal heart rate that does not respond to medication.

The treatment for baroreflex failure involves medications to control heart rate and blood pressure, as well as interventions to improve stress management.

- Diabetic autonomic neuropathy:

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy is a potential complication of diabetes. The condition affects the nerves that control the bladder, digestive system, heart, genitals, and other organs.

The symptoms include:

- resting tachycardia, which is a fast-resting heart rate

- orthostatic hypotension, or low blood pressure when standing

- constipation

- breathing problems

- gastroparesis, which refers to food not passing correctly through the stomach

- erectile dysfunction

- sudomotor dysfunction, or irregularities with sweating

- impaired neurovascular function

- “brittle diabetes,” which is characterized by frequent episodes of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia

The treatment for diabetic autonomic neuropathy focuses on the careful management of diabetes. In some cases, doctors may recommend treatments to control specific symptoms.

How is Dysautonomia Diagnosed?

The diagnosis of dysautonomia depends on the overall function of three autonomic functions – cardiovagal, adrenergic, and sudomotor. A diagnosis should, at a bare minimum, include measurements of blood pressure and heart rate while lying flat, and after at least 3 minutes of standing.

The best way to achieve a diagnosis includes a range of testing, notably an autonomic reflex screen, tilt table test, and testing of the sudomotor response (ESC, QSART, or thermoregulatory sweat test).

One of the tests your healthcare provider will use to diagnose some forms of dysautonomia is a tilt table test.

During this test:

- You lie on a table that can lift and lower at different angles. It has supports for your feet.

- You are connected to medical equipment that measures your blood pressure, oxygen levels, and heart’s electrical activity.

- When the table tilts upward, the machines measure how your body regulates ANS functions like blood pressure and heart rate.

Other tests your healthcare provider may use to aid in the diagnosis include sweating tests, breathing tests, lab (blood work) tests, and heart workup (electrocardiography). Other tests may be done to determine if other diseases or conditions are causing dysautonomia.

Additional tests and examinations to determine a diagnosis of dysautonomia include:

- Valsalva maneuver

- Ambulatory blood pressure and EKG monitoring

- Cold pressor test

- Deep breathing

- Electrochemical skin conductance

- Hyperventilation test

- Nerve biopsy for small fiber neuropathy

- Quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test (QSART)

- Testing for orthostatic intolerance

- Thermoregulatory sweat test

- Tilt table test

- Valsalva maneuver

- Tests to elucidate the cause of dysautonomia can include:

- Evaluation for acute (intermittent) porphyria.

- Evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid by lumbar puncture

How is Dysautonomia Managed or Treated?

There’s no cure for this condition, but you can manage the symptoms. Secondary forms may improve with the treatment of the underlying disease. In many cases treatment of primary dysautonomia is symptomatic and supportive.

Measures to combat orthostatic hypotension include elevation of the head of the bed, water bolus (rapid infusion of water given intravenously), a high-salt diet, and drugs such as fludrocortisone and midodrine.

Your healthcare provider may suggest many different therapies to manage your particular dysautonomia symptoms.

The more common treatments include:

- Drinking more water every day: Ask your healthcare provider how much you should drink. Additional fluids keep your blood volume up, which helps your symptoms.

- Adding extra salt (3 to 5 grams/day) to your diet: Salt helps your body keep a normal fluid volume in your blood vessels, which helps maintain normal blood pressure.

Alternative treatment

There are no alternative treatments that can cure dysautonomias, but complementary therapies may help people manage and cope with their symptoms. People may benefit from:

- Mindfulness techniques: People with dysautonomia may experience anxiety. Adding calming mindfulness practices to the daily routine may help. These could include yoga, meditation, and breathing exercises.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): Therapists use this technique to help people overcome patterns of thinking that can contribute to anxiety, worry, and stress.

- Cannabidiol (CBD): This compound comes from the hemp plant, but unlike cannabis itself, it does not cause a “high.” A small 2017 study of 12 females with dysautonomic syndrome following human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination took CBD over a 3-month period. At the end of the study, the eight participants who completed the trial reported significantly reduced body pain and improved physical, vitality, and social functioning scores. Although early research on CBD is promising, further studies are necessary to confirm the benefits, as this trial was extremely small and included only female participants aged 12–24 years.

- Sleeping with your head raised in your bed (about 6 to 10 inches higher than your body).

- Taking medicines such as fludrocortisone and midodrine to increase your blood pressure.

The treatment of dysautonomia can be difficult; since it is made up of many different symptoms, a combination of drug therapies is often required to manage individual symptomatic complaints.

Therefore, if an autoimmune neuropathy is the case, then treatment with immunomodulatory therapies is done, or if diabetes mellitus is the cause, control of blood glucose is important. Treatment can include proton-pump inhibitors and H2 receptor antagonists used for digestive symptoms such as acid reflux.

For the treatment of genitourinary autonomic neuropathy, medications may include sildenafil3https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles (a guanine monophosphate type-5 phosphodiesterase inhibitor). For the treatment of hyperhidrosis, anticholinergic agents such as trihexyphenidyl or scopolamine can be used, also an intracutaneous injection of botulinum toxin type A can be used for management in some cases.

Balloon angioplasty, a procedure referred to as trans-vascular autonomic modulation, is specifically not approved for the treatment of autonomic dysfunction.

When Should You Call the Doctor?

Contact your doctor if you experience symptoms of dysautonomia, especially frequent dizziness or fainting.

What Questions Should You Ask the Doctor?

If you have dysautonomia, you may want to ask your doctor:

- How serious is the type of dysautonomia I have?

- What part of my ANS does the disorder affect?

- What type of treatment and lifestyle adjustments are best for me?

- What signs of complications should I look out for?

- What might I expect to happen to my health in the future?

- What kinds of support groups are available?

What are the Complications of Dysautonomia or its Treatment?

Just as every person’s life is unique, everyone’s experience with dysautonomia is, too. Dysautonomia is a complex set of conditions, and the effects they have on a person’s life vary greatly depending on individual circumstances.

About 25% of those with POTS have severe symptoms that prevent them from working, sleeping, and spending time with friends and family. Some people may be unable to do much physical activity.

Dysautonomia can also affect a person’s mental health. For example, depression and increased anxiety are common among those with POTS.

The complications of dysautonomia vary depending on the symptoms you experience. In severe cases, people might have life-threatening complications such as pneumonia and respiratory failure.

Dysautonomia has a complicated relationship with other conditions. These include:

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): In PTSD, psychological trauma causes the ANS to stop functioning as it should, causing mental and physical symptoms that have a significant crossover with dysautonomia.

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): When someone has OSA, their breathing repeatedly stops and starts while they sleep. A 2019 study notes that people with OSA have ANS alterations but concludes that more research is necessary to understand the link.

- Vitamin deficiencies: Experts believe that vitamin D may play a role in autonomic disorders. Although they are unsure of the exact mechanism, it seems that low vitamin D levels can cause some of the symptoms that doctors see in people with dysautonomia.

Dysautonomia can also cause:

- Abnormal heart rate (too fast, too slow, or irregular).

- Fainting.

- Breathing trouble.

- Digestive problems.

- Visual problems, such as blurred vision.

How can Dysautonomia be Prevented?

You can’t prevent dysautonomia. You can take steps to manage your symptoms and keep them from getting worse. See the upcoming section below; “Living With Dysautonomia ” for tips and more information.

Living with Dysautonomia

What can you do to better live with dysautonomia?

To help manage your dysautonomia symptoms:

- Do not smoke or drink beverages containing alcohol.

- Eat a healthy diet.

- Drink a lot of water. Carry water with you at all times.

- Add extra salt to your diet. Keep salty snacks with you.

- Get plenty of sleep.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

- Keep your blood sugar within normal limits if you have diabetes.

- Listen to what your body is telling you it needs. For example, take breaks from work or school if your body is telling you it needs rest.

- If you feel dizzy, sit down, lie down, and/or raise your feet.

- Stand up slowly.

- Wear compression stockings and support garments to increase/maintain blood pressure

- Avoid sitting or standing for long periods of time.

- Avoid heat. Take lukewarm or cool baths and showers.

- Talk with your healthcare provider before taking any over-the-counter medicine or supplement.

- Ask your healthcare provider if you can drink caffeinated beverages or eat foods with artificial sweeteners. Caffeine should be avoided if you have a raised heart rate. Artificial sweeteners can cause migraines in some people.

The Outlook/Prognosis

The outlook for people with dysautonomia depends entirely on the specific type of condition. The term covers a wide range of conditions that vary in severity.

People with chronic, progressive, generalized dysautonomia in the setting of central nervous system degeneration have a generally poor long-term prognosis.

Death can occur from pneumonia, acute respiratory failure, or sudden cardiopulmonary arrests. Autonomic dysfunction symptoms such as orthostatic hypotension, gastroparesis, and gustatory sweating are more frequently identified in mortalities.

However, experts at leading medical institutions are carrying out revolutionary research that may offer hope to people experiencing dysautonomia.

According to some estimates, with commitment, appropriate medical treatment, and lifestyle management, the majority of those with youth-onset dysautonomia should recover or improve significantly by their mid-20s.

However, some individuals’ symptoms may return when their body is under stress, such as during pregnancy or menopause.

No one can know for sure what your life will look like living with dysautonomia. Symptoms vary from person to person. The severity of the condition varies from person to person – from mild and manageable to severe and disabling.

The course of the condition changes too – in some people, symptoms are always present; in others, symptoms appear for weeks or months, or years, disappear, and then reappear. In other words, dysautonomia is unpredictable.

Because of all these variables, it’s important to find a healthcare provider who you are comfortable with and who is knowledgeable in dysautonomia.

You may want to start a health diary to share with your healthcare provider. In this daily diary, you can record your symptoms, events that possibly triggered your symptoms, and how you are feeling emotionally. This information can help develop and tweak your plan of care.

Frequently Asked Questions About Dysautonomia

What Does Dysautonomia Feel Like?

Many dysautonomia patients have difficulty sleeping. Their physical symptoms, like racing heart rate, headache, and dizziness, combined with psychological stressors, like worry, anxiety, and guilt, get in the way of a restful night's sleep. Sleep hygiene can be improved through a number of techniques.

What is the Life Expectancy of People with Dysautonomia?

There's no cure for familial dysautonomia. People with FD have reduced life expectancies. About half of people with this condition live into their 30s. Others may live into their 70s.

How Long is Life Expectancy with POTS?

POTS is not life-threatening, and there is no evidence of reduced life expectancy.

Does Dysautonomia Shorten Lifespan?

Some forms of dysautonomia, including MSA and familial dysautonomia, are severe and shorten life expectancy.

Can POTS turn into Heart Failure?

POTS is a condition that causes your heart to beat more rapidly. But POTS isn't a heart disease and isn't likely to cause heart failure. The fact that POTS isn't life-threatening doesn't mean the condition isn't debilitating for those who experience it.

Is POTS a Serious Health Condition?

While POTS can be life-changing, it is not life-threatening. One of the biggest risks for people with POTS is falls due to fainting. Not everyone who has POTS faints. And, for those who do, it may be a rare event.

Does POTS Get Worse Over Time?

Many POTS patients will get better over time. However, some remain sick with POTS indefinitely, and some may progressively get worse. Currently, there is no cure for POTS. There are some treatments available, but they do not work for all patients

Is POTS Syndrome Life Long?

Some people have mild symptoms, while others find the condition affects their quality of life. POTS often improve gradually over time, and there are some medicines and self-care measures that can help.

Can POTS be Life Threatening?

POTS can be frightening, but it's not life-threatening. While the exact causes are often unclear, POTS symptoms are often due to a sudden surge in heart rate and the body struggling to pump blood back to the heart quickly enough.

Can You Drink Alcohol With POTS?

Avoid Alcohol: Alcohol can worsen symptoms for POTS patients. Alcohol is dehydrating and can lead to increased hypotension through dilation of the veins and thus should be avoided by most POTS patients.

What Should You Not Do with POTS Syndrome?

Avoid prolonged standing: Standing for a long time makes symptoms worse for most people with POTS. If you must stand for a long time, try flexing and squeezing your feet and muscles or shifting your weight from one foot to the other. Avoid alcohol: Alcohol can worsen symptoms because it dehydrates your body.

Do POTS Improve with Age?

The good news is that, although POTS is a chronic condition, about 80 percent of teenagers grow out of it once they reach the end of their teenage years when the body changes of puberty are finished. Most of the time, POTS symptoms fade away by age 20.

Can POTS Cause a Stroke?

There are many stories of patients who have had their levels fall into the normal range when their physicians repeatedly tested their antibodies and when told they no longer had APS and could stop their blood thinners, they went on to develop stroke or other major clotting events.

Are POTS Brain Conditions?

A neurologic disorder known as POTS causes dizziness and fainting—and frustration, due to lack of awareness and inadequate treatment.

What are Signs that POTS is Getting Worse?

Some things can make symptoms worse. These include heat, menstrual cycle, dehydration, alcohol, exercise, and standing for a long time.

What Causes POTS to Worsen?

Dehydration: Dehydration can cause or worsen POTS symptoms. Hormone problems: Changes in hormone levels, such as during pregnancy or puberty, can trigger or worsen POTS symptoms.

What Foods Can Trigger POTS?

Patients with POTS syndrome should increase their sodium intake, reduce the consumption of diuretics in their diet, and avoid alcohol and coffee. Besides natural treatments for POTS, you will also need medical treatment that your healthcare provider will prescribe.

What Do POTS Do to The Brain?

If there is not enough blood flow to the brain, a person may feel lightheaded or pass out every time they stand. In POTS, the autonomic nervous system doesn't work in the usual way, so the blood vessels don't tighten enough to make sure there is enough blood flow to the brain.

What is the Most Common Cause of POTS?

POTS often begins after a pregnancy, major surgery, trauma, or a viral illness. It may make individuals unable to exercise because the activity brings on fainting spells or dizziness.

Does POTS Show Up in Blood Work?

The trouble with diagnosing POTS is that it's currently principally a clinical diagnosis. It's based on history, the absence of other illnesses as well as the finding of an increase in heart rate when standing. There is no blood test right now to aid in the diagnosis.

What Meds Worsen POTS?

Drugs that can aggravate the symptoms of POTS are angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, α‐ and β‐blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and phenothiazines. Any such drugs should be stopped first.

Can POTS Cause Memory Loss?

One of the most common symptoms reported by POTS patients is cognitive dysfunction or “brain fog.” These terms both indicate a loss of brain functioning in areas such as thinking, remembering, concentrating, and reasoning to a level that interferes with daily activities.

How Do You Live a Normal Life with POTS?

Though there is no cure for POTS, many patients will feel better after making certain lifestyle changes, like taking in more fluids, eating more salt, and doing physical therapy.

Can You Lift Weights with POTS?

Avoid working with your arms overhead, lifting heavy objects, and climbing stairs. If these tasks must be performed, rest breaks should be taken frequently and/or assistance should be asked for.

What Trauma Causes POTS?

What Causes POTS? As we mentioned above, POTS often starts after experiencing a physical trauma, like a concussion. However, it can also appear following a pregnancy, a surgery, or even a viral illness.

Additional resources and citations

- 1ninds gov/

- 2clevelandclinic

- 3https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles