The normal state of consciousness comprises either the state of wakefulness, awareness, or alertness in which most human beings function while not asleep or one of the recognized stages of normal sleep from which the person can be readily awakened.

The abnormal state of consciousness is more difficult to define and characterize, as evidenced by the many terms applied to altered states of consciousness by various observers. Among such terms are clouding of consciousness, confusional state, delirium, lethargy, obtundation, stupor, dementia, hypersomnia, vegetative state, akinetic mutism, locked-in syndrome, coma, and brain death.

Many of these terms mean different things to different people and may prove inaccurate when transmitting and recording information regarding the state of consciousness of a patient. Nevertheless, it is appropriate to define several of the terms as closely as possible. Hence, today’s article topic is ‘level of consciousness’.

In this article, all the levels of consciousness will be explained so that you will gain adequate knowledge on the type of consciousness you or another person is experiencing and the recommended actions to do when in a particular level of consciousness.

Alright, let’s proceed.

Consciousness and the Brain

The brain is ultimately responsible for maintaining consciousness. Your brain requires certain amounts of oxygen and glucose in order to function properly.

Many substances you consume can affect your brain chemistry. These substances can help to maintain or decrease consciousness. For example, caffeine is a stimulant, which means that it raises your levels of brain activity.

Caffeine can be found in many foods and beverages you consume every day, such as coffee, soda, and chocolate. On the other hand, painkillers and tranquilizers make you drowsy. This side effect is a form of impaired consciousness.

Diseases that damage your brain cells can also cause impaired consciousness. A coma is the most severe level of consciousness impairment.

Level of Consciousness – What is it?

Level of consciousness is a term used to describe a person's awareness and understanding of what is happening in his or her surroundings.1https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Altered_level_of_consciousness

Want a video explanation on this topic? If yes, then watch the video below:

What are the Levels of Consciousness?

There are three main levels of consciousness:

- Consciousness is an awake state, when a person is fully aware of his or her surroundings and understands, talks, moves, and responds normally.

- Decreased consciousness is when a person appears to be awake and aware of surroundings (conscious) but is not responding normally. While in a state of decreased consciousness, a person may not answer when spoken to, stare straight ahead, and have no facial expression. Others may think the person is acting confused, odd, or sleepy. Later, the person may not be able to recall what happened.

- Unconsciousness is when a person is not aware of what is going on and is not able to respond normally to things that happen to and around him or her.

Other Terms Associated with Levels of Consciousness

- Fainting is a brief form of unconsciousness.

- Coma is a state of unarousable unresponsiveness or a deep, prolonged state of unconsciousness.

- General anesthesia is a controlled period of unconsciousness.

- Clouding of consciousness is a very mild form of altered mental status in which the patient has inattention and reduced wakefulness.

- A confusional state is a more profound deficit that includes disorientation, bewilderment, and difficulty following commands.

- Lethargy consists of severe drowsiness in which the patient can be aroused by moderate stimuli and then drift back to sleep.

- Obtundation is a state similar to lethargy in which the patient has a lessened interest in the environment, slowed responses to stimulation, and tends to sleep more than normal with drowsiness in between sleep states.

- Stupor means that only vigorous and repeated stimuli will arouse the individual, and when left undisturbed, the patient will immediately lapse back into the unresponsive state.

What is Decreased Consciousness?

The major characteristics of consciousness are alertness and being oriented to place and time. Alertness means that you’re able to respond appropriately to the people and things around you. Being oriented to place and time means that you know who you are, where you are, where you live, and what time it is.

When consciousness is decreased, your ability to remain awake, aware, and oriented is impaired. Impaired consciousness can be a medical emergency.

Symptoms of Decreased Consciousness

Symptoms that may be associated with decreased consciousness include:

- Seizures

- Loss of bowel or bladder function

- Poor balance

- Falling

- Difficulty walking

- Fainting

- Lightheadedness

- Irregular heartbeat

- Rapid pulse

- Low blood pressure

- Sweating

- Fever

- Weakness in the face, arms, or legs

Types of Decreased Consciousness

Levels of impaired consciousness include:

- Confusion

- Disorientation: Disorientation is the inability to understand how you relate to people, places, objects, and time. The first stage of disorientation is usually around awareness of your current surroundings (e.g., why you’re in the hospital). The next stage is being disoriented with respect to time (years, months, days). This is followed by disorientation with respect to place, which means you may not know where you are. Loss of short-term memory follows disorientation with respect to place. The most extreme form of disorientation is when you lose the memory of who you are.

- Delirium: If you’re delirious, your thoughts are confused and illogical. People who are delirious are often disoriented. Their emotional responses range from fear to anger. People who are delirious are often highly agitated as well.

- Lethargy

- Stupor

- Coma

Common Underlying Causes of Decreased Consciousness

Common causes of decreased consciousness include:

- Drugs

- Alcohol

- Substance abuse

- Certain medications

- Epilepsy

- Low blood sugar

- Stroke

- Lack of oxygen to the brain

- Other underlying causes of decreased consciousness include:

- Cerebral hemorrhage

- Dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease

- Head trauma

- Brain tumor

- Heart disease

- Heat stroke

- Liver disease

- Uremia, or end-stage kidney failure

- Shock

Diagnosis and Treatment of Decreased Consciousness

Diagnosis and treatment of decreased consciousness begin with a complete medical history and physical examination, which includes a detailed neurological evaluation. Your doctor will want to know about any medical problems you have, such as diabetes, epilepsy, or depression.

They’ll ask about any medications you’re taking, such as insulin or anticonvulsants. They’ll also ask if you have a history of abusing illegal drugs, prescription drugs, or alcohol.

In addition to your complete history and physical, the doctor may order the following tests:

- Complete blood count (CBC): This blood test reveals whether you have a low hemoglobin level, which indicates anemia. An elevated white blood cell (WBC) count indicates infections, such as meningitis or pneumonia.

- Toxicology screen: This test uses a blood or urine sample to detect the presence and levels of medications, illegal drugs, and poisons in your system.

- Electrolyte panel: These blood tests measures levels of sodium, potassium, chloride, and bicarbonate.

- Liver function tests: These tests determine the health of your liver by measuring levels of proteins, liver enzymes, or bilirubin in your blood.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): This exam uses scalp electrodes to evaluate brain activity.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG): This exam measures your heart’s electrical activity (such as heart rate and rhythm).

- Chest X-ray: Doctors use this imaging test to evaluate the heart and lungs.

- CT scan of the head: A CT scan uses computers and rotating X-rays to make high-resolution images of the brain. Doctors use these images to find abnormalities.

- MRI of the head: An MRI uses nuclear magnetic resonance imaging to make high-resolution images of the brain.

Treating Decreased Consciousness

Treatment for decreased consciousness depends on what’s causing it. You may need to change medications, begin a new treatment, or simply treat the symptoms to address the underlying cause.

For example, you need emergency medical treatment and possibly surgery to treat a cerebral hemorrhage. On the other hand, there’s no cure for Alzheimer’s. In this case, your healthcare team will work with you to come up with strategies to treat symptoms and maintain the quality of your life for as long as possible.

Talk to your doctor as soon as you think you may be experiencing decreased consciousness. They can start your treatment as soon as possible.

Altered Level of Consciousness

An altered level of consciousness is any measure of arousal other than normal. Level of consciousness (LOC) is a measurement of a person's arousability and responsiveness to stimuli from the environment.

A mildly depressed level of consciousness or alertness may be classed as lethargy; someone in this state can be aroused with little difficulty. People who are obtunded have a more depressed level of consciousness and cannot be fully aroused.

Those who are not able to be aroused from a sleep-like state are said to be stuporous. Coma is the inability to make any purposeful response. Scales such as the Glasgow coma scale have been designed to measure the level of consciousness.

An altered level of consciousness can result from a variety of factors, including alterations in the chemical environment of the brain (e.g. exposure to poisons or intoxicants), insufficient oxygen or blood flow in the brain, and excessive pressure within the skull. Prolonged unconsciousness is understood to be a sign of a medical emergency.

A deficit in the level of consciousness suggests that both of the cerebral hemispheres or the reticular activating system have been injured. A decreased level of consciousness correlates to increased morbidity (sickness) and mortality (death). Thus, it is a valuable measure of a patient's medical and neurological status. In fact, some sources consider the level of consciousness to be one of the vital signs.

Diagnosis of Altered Level of Consciousness

Assessing LOC involves determining an individual's response to external stimuli. Speed and accuracy of responses to questions and reactions to stimuli such as touch and pain are noted.

Reflexes, such as the cough and gag reflexes, are also means of judging LOC. Once the level of consciousness is determined, clinicians seek clues for the cause of any alteration.

Usually, the first tests in the ER are pulse oximetry to determine if there is hypoxia, and serum glucose levels to rule out hypoglycemia. A urine drug screen may be sent. A CT head is very important to obtain to rule out bleeding. In cases where meningitis is suspected, a lumbar puncture must be performed.

A serum TSH is an important test to order. In select groups consider vitamin B12 levels. Checking serum ammonia is particularly advised in a neonatal coma to discern inborn errors of metabolism.

Differential diagnosis

A lowered level of consciousness indicates a deficit in brain function. The level of consciousness can be lowered when the brain receives insufficient oxygen (as occurs in hypoxia); insufficient blood (as occurs in shock, in children for example due to intussusception); or has an alteration in the brain's chemistry.

Metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus and uremia can alter consciousness. Hypo- or hypernatremia (decreased and elevated levels of sodium, respectively) as well as dehydration can also produce an altered LOC.

A pH outside of the range the brain can tolerate will also alter LOC. Exposure to drugs (e.g. alcohol) or toxins may also lower LOC, as may a core temperature that is too high or too low (hyperthermia or hypothermia). Increases in intracranial pressure (the pressure within the skull) can also cause altered LOC.

It can result from traumatic brain injury such as concussion. Stroke and intracranial hemorrhage are other causes. Infections of the central nervous system may also be associated with decreased LOC; for example, an altered LOC is the most common symptom of encephalitis.

Neoplasms within the intracranial cavity can also affect consciousness, as can epilepsy and post-seizure states. A decreased LOC can also result from a combination of factors. A concussion, which is a mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) may result in decreased LOC.

Treatment of Altered Level of Consciousness

Treatment depends on the degree of decrease in consciousness and its underlying cause. Initial treatment often involves the administration of dextrose if the blood sugar is low as well as the administration of oxygen, naloxone, and thiamine.

Measuring the Levels of Consciousness

It is helpful to have a standard scale by which one can measure levels of consciousness. This proves advantageous for several reasons: Communication among healthcare personnel about the neurologic condition of a patient is improved; guidelines for diagnostic and therapeutic intervention in certain situations can be linked to the level of consciousness.

And in some situations, a rough estimate of prognosis can be made based partly on the scale score. In order for such a scale to be useful it must be simple to learn, understand, and implement. Scoring must be reproducible among observers.

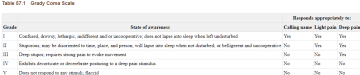

The Grady Coma Scale (shown below) has proved functional in this regard. It has been used in many hospitals to gauge the level of consciousness of patients in the neurosurgical intensive care unit and elsewhere.

The grade I patient is only slightly confused. The grade II patient requires a light pain stimulus (such as a sharp pin tapped lightly over the chest wall) for appropriate arousal or may be combative or belligerent.

The grade III patient is comatose2Fisher CM. The neurological examination of the comatose patient. Acta Neurol Scand. 1969;45 (Suppl 36):1–56. [PubMed] but will ward off deeply painful stimuli such as sternal pressure or nipple twist with an appropriate response. The grade IV patient reacts inappropriately with either decorticate or decerebrate posturing to such deeply painful stimuli, and the grade V patient remains flaccid when similarly stimulated.

Many other coma scales have been developed. Most are tailored to specific subsets of patients and are designed not only to reflect the level of consciousness but also to include additional data so that more reliable comparisons can be made for research purposes or more reliable prognostic determinations can be made.

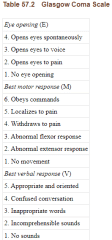

An example of such a scale is the Glasgow Coma Scale which is indicated below. In this scale, the normal state merits a score of 15, and as the level of consciousness.

Technique for Measurement of Patients with Altered Levels of Consciousness

The technique of evaluation of a patient with an altered level of consciousness can be divided into three phases. The first is to determine the level of consciousness itself. Second is the evaluation of the patient, searching carefully for hints as to the cause of the confusion or coma.

The third is the presence or absence of focality of the disorder, both in terms of the level of dysfunction within the rostrocaudal neuraxis and the specific involvement of cortical or brainstem structures.

After the physician makes sure that no immediate life-threatening emergency such as airway obstruction or shock is present, the examination begins with observation of the patient.

What is the position of the patient? Does the patient have one or more extremities positioned in an unusual manner, which might suggest paralysis or spasticity? Are the eyes opened or closed? Does the person acknowledge your presence, or is he or she oblivious to it? If the patient is alert, acknowledges the presence of the examiner, seems well-oriented to time and place, and is not confused on general questioning, then the level of consciousness would be considered normal.

Thus, one can have a normal level of consciousness yet be of subnormal intellectual capability, have a focal neurologic deficit such as aphasia or hemiparesis, or exhibit abnormal thought content such as a schizophrenic patient might.

As the patient's name is called in a normal tone of voice or if, during an attempt at a simple conversation, it is noted that the person is confused, drowsy, or indifferent, an abnormal level of consciousness exists.

Individuals who respond with recognition when their name is called and do not lapse into sleep when left undisturbed can be said to be in a grade I coma. If the alteration in level of consciousness is more severe so that the person lapses into sleep when not disturbed and is arousable only when a pin is tapped gently over the chest wall, the grade of coma is II.

This category also includes the patient who is organically disoriented, belligerent, and uncooperative (as can be seen in various states of intoxication), or the young adult with a moderately severe head injury.

If such efforts as calling the patient's name in a normal tone of voice or pricking the skin over the chest wall lightly with a pin result in no response, the examiner must choose a deeper pain stimulus. My preference is a pinch or slight twist of the nipple.

Other options include sternal pressure, which may be applied with the fisted knuckle, or squeezing the nail bed. The slight periareolar bruising from repetitive nipple twisting is much less problematic to the eventually recovered patient than the chronically painful subperiosteal or subungual hemorrhage from the latter options.

Under no circumstances should one apply such a painful stimulus as irrigation of the ears with ice water until the status of the intracranial pressure is known. The patient's response to the deep pain stimulus is then noted.

A patient who winces and/or attempts to ward off the deep pain stimulus appropriately can be said to be in a grade III coma.

The deep pain stimulus may, however, result in abnormal postural reflexes, either unilateral or bilateral. The two most common are decorticated and decerebrated posturing.

In both states, the lower extremity exhibits extension at the knee and internal rotation and plantar flexion at the ankle. In decorticate posturing, the upper extremity is held adducted at the shoulder and flexed at the elbow, wrist, and metacarpal-phalangeal joints.

In the decerebrate state, the upper extremity is adducted at the shoulder and rigidly extended and internally rotated at the elbow. In either case, the patient exhibiting such posturing to a deep pain stimulus is rated a grade IV coma. The patient who maintains a state of flaccid unresponsiveness despite deep pain stimulation is in a grade V coma.

Once the level of consciousness is determined, a careful check for hints as to the cause of the alteration in the level of consciousness should be undertaken. In most instances, the history (which can be obtained from the patient or those who accompany him, or from available medical records) is more valuable than the examination.

History is not always available, however, and in all instances, a careful examination is merited. Vital signs may obviously suggest infection, hypertension, shock, or increased intracranial pressure with bradycardia. Is there evidence of trauma to the head or elsewhere? Inspect the scalp thoroughly for abrasions or contusions, and if blood is seen, explain it even if it means shaving part of the scalp to do so.

Is there periorbital or retro-auricular ecchymosis, or is there blood behind the tympanic membrane to suggest basilar skull fracture? Is there papilledema or intraocular hemorrhage? Is the conjunctiva icteric, the liver enlarged, or does the patient have asterixis? Are the lips or nail beds discolored or pale so as to suggest anemia or pulmonary dysfunction?

Is the neck stiff—a warning of meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage? Is there anything to suggest intoxication with drugs or poisons, such as an unusual odor to the breath or body or pinpoint pupils?

The next step is to try to localize the problem that is resulting in the alteration of consciousness, first by trying to localize the dysfunction to a level within the rostrocaudal neuraxis and second by searching for focal clues such as specific cranial nerve deficits, abnormal reflexes, or motor asymmetry.

The level of consciousness determines to a certain extent the level of functional disturbance within the neuraxis. A patient who qualifies as a grade I or II has cortical or diencephalic dysfunction. The grade III patient has physiologic dysfunction above the midbrain. Grade IV coma indicates dysfunction above the levels of the cerebral peduncles or pons, and with grade V coma the medulla may be all that is working.

Observation of the pattern of respiration may further support the examiner's impression of a dysfunctional level. Cheyne-Stokes respiration means trouble at or above the diencephalon; central neurogenic hyperventilation (which is rare) points to difficulty at the upper midbrain; apneustic respiration suggests functional pontine deficit, and an ataxic breathing pattern suggests dorsomedial medullary dysfunction.

Observation of the rate, pattern, and depth of respiration over at least several minutes is necessary to document such alterations. Like respiratory patterns, the size and reactivity of the pupils can be used to substantiate further the level of dysfunction within the neuraxis.

Small reactive pupils suggest diencephalic localization, frequently on a metabolic basis. Large pupils that dilate and contract automatically (hippus) but do not react to direct light stimulus suggest a tectal lesion. Mid-position fixed pupils localize to the midbrain. Bilateral pinpoint pupils are indicative of pontine trouble.

Examination of the so-called brainstem reflexes is of utmost importance in the evaluation of the patient in grade III, IV, or V coma (Table 57.5). All rely on the integrity of centers within the pons or dorsal midbrain.

As emphasized earlier, the cold-water caloric test should not be done until the status of the patient's intracranial pressure is known. Irrigation of the eardrum with ice water causes such pain that the patient's Valsalva response may be enough to initiate herniation in the already tenuous situation of markedly increased intracranial pressure.

Further examination may be productive in revealing findings such as a unilateral dilated pupil, a focal cranial nerve deficit, an asymmetry of movement suggesting a hemiparesis, abnormal movements suggesting seizure activity, a reflex asymmetry, or a focal sensory abnormality that will help further localize the area of trouble within the central nervous system.

The Outlook and Clinical Significance

Decreased consciousness can be a sign of a serious condition. Getting prompt medical attention is important for your long-term outlook. Your outlook can become worse the longer you spend in less than full consciousness.

At all times when evaluating the patient with an alteration in level of consciousness, the clinician must keep foremost in his or her mind the most common causes of coma.

Leading the list are the various metabolic and toxic disturbances of the brain such as acid–base disequilibrium, disorders of oxygen or glucose metabolism, uremic and hepatic encephalopathy, drug overdose, and poison ingestion.

Epilepsy and various post-convulsive states can present as altered consciousness. Cerebrovascular disorders such as ischemic or embolic stroke, and intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage are also common causes of stupor or coma. Infection (meningitis, cerebral abscess, or encephalitis) can be the culprit.

Intracranial sequelae of head injury frequently result in alteration in consciousness, as can brain tumors3Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage: a practical scale. Lancet. 1975;1:480–84. [PubMed], either primary or metastatic. On occasion, two or more etiologies may be operating; for instance, the alcoholic who presents in a grade II coma with both an elevated blood alcohol level and a subdural hematoma.

Consequently, history is important in the diagnosis of the causes of altered levels of consciousness. Knowledge of the temporal course and sequence of symptom evolution, or the presence of associated disease states, is most helpful.

By taking a systematic approach to the evaluation of the confused, obtunded, or comatose patient, much can be inferred regarding possible etiologies. First, one determines the level of coma, then searches for physical signs that might point to causes, and then further localizes the level of dysfunction within the neuraxis.

The information gathered in such an assessment will serve to tailor the subsequent diagnostic and therapeutic steps.

All right, guys, that is it for now for the level of consciousness. I hope Healthsoothe answered any questions you had concerning the levels of consciousness.

Feel free to contact us at contact@healthsoothe.com if you have further questions to ask or if there’s anything you want to contribute or correct to this article. And don’t worry, Healthsoothe doesn’t bite.

And always remember that Healthsoothe is one of the best health sites out there that genuinely cares for you. So, anytime, you need trustworthy answers to any of your health-related questions, come straight to us, and we will solve your problem(s) for you.

I Am odudu abasi a top-notch and experienced freelance writer, virtual assistant, graphics designer and a computer techie who is adept in content writing, copywriting, article writing, academic writing, journal writing, blog posts, seminar presentations, SEO contents, proofreading, plagiarism/AI checking, editing webpage contents/write-ups and WordPress management.

My work mantra is: “I can, and I will”

Additional resources and citations

- 1https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Altered_level_of_consciousness

- 2Fisher CM. The neurological examination of the comatose patient. Acta Neurol Scand. 1969;45 (Suppl 36):1–56. [PubMed]

- 3Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage: a practical scale. Lancet. 1975;1:480–84. [PubMed]

The content is intended to augment, not replace, information provided by your clinician. It is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice. Reading this information does not create or replace a doctor-patient relationship or consultation. If required, please contact your doctor or other health care provider to assist you to interpret any of this information, or in applying the information to your individual needs.