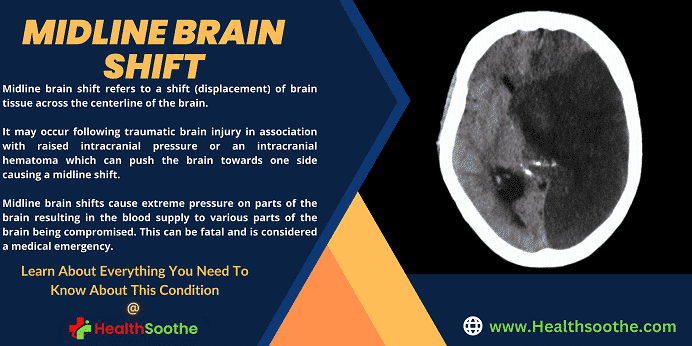

On transverse (axial) slices from MRI and CT scans, the midline shift is a phenomenon that is documented.

As a result of pushing or pulling forces on either side of the intracranial compartment, midline shift is the term used to describe a situation in which the midline of the intracranial anatomy is no longer in the midline.

Midline shift was formerly measured on a frontal radiograph of the skull by the displacement of the calcified pineal gland. This was before the development of cross-sectional imaging.

The perpendicular distance between a midline structure, typically the septum pellucidum, and a line designated as the midline is known as the midline shift and is measured in millimetres.

The midline, which is best represented as a line drawn between the anterior and posterior attachments of the falx to the inner table of the skull, is thought to be coplanar with the falx cerebri.

If the ventricles or the falx are already asymmetrical, caution must be exercised. A line between the free edges of the anterior and posterior falx can be used as an alternative if the falx is not straight.

If the superior sagittal sinus is truly midline and not coursing to one side, as is occasionally observed with a dominant transverse sinus, it can also be used to indicate the posterior falcine attachment.

The conditions of severe brain injury, stroke, haemorrhage, brain edema, or birth abnormality that increases intracranial pressure may all result in midline displacement. The cingulate gyrus is often displaced under the free margin of the falx cerebri by a unilateral frontal, parietal, or temporal lobe mass effect, and this condition is known to cause a variety of neurological issues.

The midline shift indication is seen as concerning since it is often linked to a brain stem distortion that may result in major malfunction as shown by aberrant posture and a failure of the pupils to dilate in response to light. High intracranial pressure (ICP), which may be fatal, is often linked to midline displacement.

Midline shift is really a way to monitor intracranial pressure (ICP), and the presence of midline shift is a sign that ICP is elevated. Midline shift is a sign that neurosurgeons should take action to monitor and manage ICP.

A variety of traumatic brain lesions, including extra- and subdural hematomas and traumatic parenchymal lesions, have significant midline displacement (> 5 mm) as a crucial indication for surgical therapy.

The Monro-Kellie concept, which holds that the cranial volume in an adult is constant, is shown by the displacement of the brain parts mentioned above. Most of the brain, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and blood arteries make up the cranial contents.

If a mass, such as a tumour, edema, or hematoma, develops, these components must change position to make room for the mass. A portion of the cerebral contents will herniate through the tentorial incisura to accommodate the bulk since the cranial volume remains constant.

The CSF gaps often increase in size to cover the hole in a patient who has lost brain mass, such as is the case after a stroke.

Midline shift brain causes

- head injury (epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, intracerebral haemorrhage or contusions)

- The three biggest causes of head trauma are attacks, falls, and motor vehicle-related injuries 9.

- Head trauma is divided into three categories based on the mechanism: blunt (a most frequent mechanism), piercing (most deadly injuries), and blast.

- The majority of serious traumatic brain injuries are caused by falls and auto accidents.

- brain cancer

- Stroke

- Non-traumatic intracranial bleeding (aneurysm rupture)

- benign or idiopathic intracranial hypertension

- Hydrocephalus

- Meningitis

Midline shift brain symptoms

The main causes of elevated intracranial hypertension symptoms are papilledema and neurological irritation, compression, or displacement. Almost all cases of non-specific headaches are recorded, and they are probably mediated by the trigeminal nerve's pain fibres in the dura and the brain's blood vessels. Pain is typically diffuse and worse in the mornings, and the Valsalva manoeuvre can exacerbate it.

Vomiting and nausea are frequent symptoms of high intracranial pressure. Patients who have CN VI palsy from compression and horizontal diplopia are more likely to present with double vision.

Frequent transient visual abnormalities can cause one or both eyes to gradually lose vision, which is how they are frequently described. The worsening of visual anomalies is caused by posture changes.

It is possible to report peripheral vision loss, which typically starts in the nasal inferior quadrant and progresses to loss of the central visual field. Visual acuity changes that include blurring or distortion could happen.

There may be varying degrees of colour distinction loss. Intraocular haemorrhage can cause a sudden loss of vision in more severe or chronic cases.

It is possible to experience pulsing tinnitus that is made worse by supine or bending positions and the Valsalva manoeuvre. Radicular pain, numbness, or paresthesias are potential symptoms that are frequently linked to localised compression of the brain or potential brain herniation. Neurological findings can indicate a serious illness.

The subfalcine, central transtentorial, uncal transtentorial, cerebellar tonsillar/foramen magnum, and transcalvarial lobes are the anatomical regions where the herniation is most likely to happen.

Consciousness or responsiveness may decline as a result of these kinds of changes. Depending on whatever part of the brain has herniated, specific neurological constellations may exist.

Due to the local impact of mass lesions or pressure on the reticular formations of the midbrain, this often ends in a stupor state or more seriously in a coma. It could also result in respiratory impairment.

- Difficulty maintaining balance.

- A constant sense of imbalance.

- Inappropriate posture.

- Efficient weight distribution on the balls of the feet.

- Abnormal gait or walk.

- Changes in the sense of direction.

- “Odd” perceptions of one's position in space

Midline shift brain treatment

An intensive care unit (ICU) environment requires constant monitoring in the event of a rapid rise in intracranial pressure, which is a neurosurgical emergency.

A patient with acute intracranial hypertension should initially be stabilised, with medical personnel working for hemodynamic stability and avoiding and addressing any aggravating or precipitating causes.

These patients need to have their heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, oxygenation, ventilation, blood glucose, input, and ECG closely monitored. Monitoring of intracranial pressure should also be performed in patients with suspected intracranial hypertension, particularly those with severe traumatic brain injury.

It is crucial to avoid and address conditions that could worsen or trigger intracranial hypertension. These measures are taken to buy time until the underlying cause is found and fixed.

- To reduce venous outflow resistance and enhance cerebral spinal fluid displacement from the intracranial to the spinal compartment, keep the head neutrally positioned and elevated to 30 degrees.

- Intracranial pressure may rise in both hypoxia and hypercapnia. It is essential to manage your breathing properly to keep your intracranial pressure under control. To maintain a normal PaCO2 and sufficient oxygenation without raising the PEEP, ventilation control is crucial.

- Blood pressure and intracranial pressure can both rise as a result of agitation and pain. An essential adjunctive treatment is providing adequate analgesia and sedation. Medication with a negligible hypotensive effect should be preferred because the majority of sedatives can affect blood pressure.

Before giving out sedatives, hypovolemia should be treated because it can hasten the hypotensive side effects. The advantage of shorter-acting drugs is that sedation can be briefly interrupted to assess neurological status.

- Fever can speed up the metabolism of the brain and is a powerful vasodilator, both of which increase cerebral blood flow and intracranial pressure. Antipyretics and cooling blankets should be used to reduce fever, and infectious causes must be ruled out.

Conclusion:

Depending on the source, midline shift symptoms might range from benign to fatal. Children often have a longer tolerance for increased intracranial pressure (ICP).