Introduction to the Trochanter

Quick Facts About The Trochanter

| A | B |

|---|---|

| Definition | A trochanter is a tubercle of the femur near its joint with the hip bone |

| Location | Upper part of the femur (thigh bone) near the hip joint |

| Function | Serves as important muscle, ligaments, and tendons attachment sites in humans and most mammals |

| Types in Human | Greater trochanter, Lesser trochanter, and occasionally a Third trochanter |

| Greater Trochanter | Larger and more prominent, located on the outer part of the upper femur |

| Lesser Trochanter | Smaller and located on the lower back part of the femur |

| Third Trochanter | Inconsistent presence, located on the posterior aspect of the femur |

| Etymology | Derived from Greek “Trokhos” meaning “wheel”, referring to the spherical femoral head |

| In Other Animals | Fourth trochanter in archosaur leg bones; segment of the arthropod leg |

| Related Anatomy | Intertrochanteric crest, Intertrochanteric line |

| Clinical Relevance | Attachment site for muscles like the iliopsoas group, which are involved in flexion of the trunk and thigh |

A trochanter is a femoral tubercle at the hip bone's joint. It is a bony protrusion towards the bottom of the thighbone (femur). Trochanters are essential muscle attachment sites in humans and other animals.

Humans are recognized to have 3 trochanters, yet only the larger and lesser trochanters are anatomically "normal." (Not all specimens have the third trochanter.)

The Structure and Function of the Trochanter

As we have established earlier; we have 3 types of trochanters. They are:

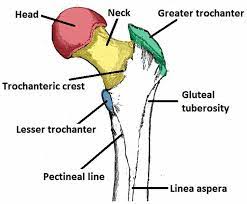

- Greater trochanter: A strong protrusion at the proximal (near) & lateral (outside) end of the femur shaft. The larger trochanter is also considered as the major trochanter, the external trochanter, and the femoral lateral process.

- Lesser trochanter: A pyramidal protrusion that arises from the proximal (near) & medial (inner) femoral shaft1Moore KL (1992) The Lower Limb. In: Clinically Oriented Anatomy, (3rd edn); edited by Moore KL, Williams and Wilkins, USA, pp. 373-495.. The lesser trochanter is often known as the minor trochanter, the internal trochanter, and the femoral medial process.

- Third trochanter, which is occasionally present.

Trochanters are attachment places for hip and thigh muscles. A variety of muscles (including gluteus minimus & medius, gemelli muscles, and externus, piriformis and obturator internus) connect to the greater trochanter2Schuenke M, Schutle E, Schumacher U (2006) Lower Limb: Bones, ligaments and joints. In: THIEME Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System, (1st edn); edited by Ross L, Lamperti E, Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart; New York, USA, pp. 360-418., whereas numerous muscles input into the lesser trochanter (including the iliacus muscles and psoas major)3Damien P Byrne, Kevin J Mulhall, Joseph F Baker (2010) Anatomy & Biomechanics of the Hip. Open Sports Med J 4(1): 51-57..

The Embryology and Formation of the Trochanter

Three weeks after fertilization, primitive limb buds are already beginning to form in the embryo. Strayer demonstrated that these are initially filled with mesenchyme which differentiates in time to form all joint components except for the blood vessels and nerves.

The 6-week embryo is 12mm long. Areas within the mesenchyme have condensed to outline the ilium, ischium, pubis, and femoral shaft. Rapid differentiation follows. The femoral head appears slightly later than the femoral shaft but by 7 weeks, when the embryo is 17mm long, an inter-zone develops between the femoral head and the acetabulum.

Three separate layers develop within this inter-zone and come to form the perichondrium of the acetabulum and the femoral head together with the synovial membrane.

By 8 weeks the embryo is 30mm long and blood vessels have grown into the ligamentum teres. There is the beginning of angulation of the femoral neck upon the femoral shaft. The cleft which heralds the true joint cavity begins to develop by apoptosis and the acetabular labrum is identifiable as a separate entity.

At 11 weeks the embryo is 50mm long. The femoral head is spherical and 2mm in diameter. It is clearly separate from the acetabulum and Watanabe (1974) showed that it was possible experimentally to dislocate the hip for the first time at this age.

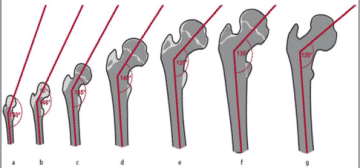

The NSA now measures 140-1500; it is already possible to detect femoral anteversion between 5 and 100; the vascular supply to the hip is established. The 16-week fetus is 120mm long.

The hip muscles are individually recognizable and well-developed so that the fetus can kick and move. The femoral shaft shows early ossification within its cartilage anlage but the femoral head and trochanters remain cartilaginous until well after birth.

In utero, fetal hips lie typically in flexion, abduction, and external rotation, with the left hip, usually being the more rotated. The blood supply to the femoral head is predominantly through the epiphyseal and metaphyseal vessels.

The vessels in the ligamentum teres are insignificant at this stage but contribute more to the femoral head blood supply later in gestation. During the last 20 weeks of intra-uterine life, the hip joint enlarges and matures.

Acetabular growth is complex: the triradiate cartilage contributes 70%, enlarging both in diameter and depth. At the interface between the pelvic bones and the triradiate cartilage, double-growth plates allow the circumferential enlargement of the cavity to accommodate the growing femoral head. Growth plates extend also beneath the articular surface of each pelvic bone.

The acetabular ring epiphysis which surrounds the acetabular margin contributes nearly 30% to acetabular depth. Small centers of ossification appear in the ring epiphysis between 11 and 14 years. It usually fuses to the acetabular margin in mid-adolescence.

The triradiate cartilage closes at about 11 years in girls and a year later in boys. Development of the proximal femoral chondroosseous epiphysis and physis is probably the most complex of all the appendicular skeletal growth regions.

There are several stages in the development of the proximal femur4Ogden JA (1983) Development and growth of the hip. In: Management of Hip Disorders in Children, edited by Katz JE, Siffert RS (Eds.); Lippincott, Philadelphia, p. 1-32.. Perhaps the two most important features are the continuity of epiphyseal and physeal cartilage along the posterosuperior neck throughout much of postnatal development and the intracapsular course of the limited capital femoral blood vessels.

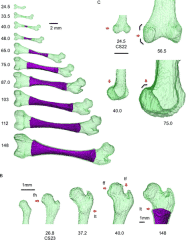

Secondary ossification usually begins in the capital femur by 4-6 months postnatally (range 2-10 months). This process is a centrally located sphere of ossification that expands centrifugally, eventually conforming to the hemispheric shape of the articular surface by the time the child is 6-8 years old and forming a discrete subchondral plate that follows the capital femoral physeal contour.

Throughout most of the development, the capital femoral and trochanteric epiphyses have a cartilaginous continuity along the posterior and superior portions of the femoral neck.

Although this region gradually thins as the child grows, it is essential for the normal latitudinal growth of the femoral neck and, in part, the normal decrease in anteversion. Selective growth along the capital femoro-intertrochanteric physis establishes a discrete femoral neck.

The primary spongiosa initially formed during neck development is not completely oriented to biological forces across the hip joint. The more responsive secondary spongiosa begins to form the typical trabecular patterns oriented to compression and tension forces.

This process becomes more prominent during the second decade of life. The area between these major osseous patterns is often referred to as Ward’s triangle. The development of the femoral neck brings about changes in the contour of the capital femoral physis.

Initially, the femoral neck is transversely directed, but during the first year, there is preferential growth in the medial, and middle sections. As these regions develop, the capital femoral physis becomes more medially (Varus) and posteriorly oriented, which eventually may predispose to slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

Lappet formation, undulations, and mammillary processes develop in the physis, again becoming more evident after 10 years of age. These processes and contours serve to “anchor,” or stabilize, the capital femoral epiphysis to prevent displacement due to biologic shear stresses.

Ossification begins in the greater trochanter at 5-7 years (Figure 3) and is initially present directly above the trochanteric physis. With further development, ossification proceeds cephalad into the remainder of the epiphysis. Epiphysiodesis of the greater trochanter occurs at 14-16 years (usually later than in the capital femoral physis).

The lesser trochanter does not usually ossify until adolescence (Figure 3). Fusion occurs between 15 and 19 years. This region is subject to high tensile stresses from the attached iliopsoas tendon and represents a traction apophysis. Overgrowth may occur owing to chronic stress, as with cerebral palsy.

The Blood Supply and Lymphatics of the Trochanter

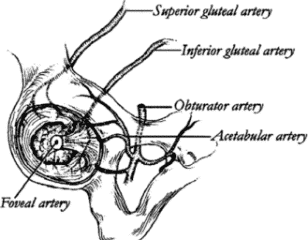

The hip joint receives its blood supply from several sources. The acetabulum is supplied by three main arteries: the obturator, the superior gluteal, and inferior gluteal. The superior gluteal artery supplies both the superior and posterior portions of the acetabulum, and the inferior gluteal artery supplies the inferior and posterior portions.

The acetabular branch of the obturator artery provides the primary blood supply to the medial aspect of the acetabulum. A smaller, terminal branch of the posterior division of the obturator artery, known as the foveal artery, traverses the ligamentum teres to supply a small area of the femoral head around the fovea centralis.

The recess between the capsule and labrum is lined with highly vascularized, loose connective tissue. A group of three to four small blood vessels is found in a circumferential pattern within the substance of the labrum and along the labrumbone junction.

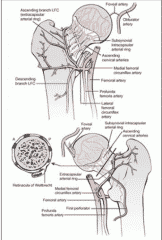

The arterial supply to the proximal end of the femur has been studied extensively. The description by Crock seems the most appropriate because it is based on a three-plane analysis and provides a standardization of anatomic nomenclature.

Crock described the arteries of the proximal end of the femur in three groups:

- an extracapsular arterial ring located at the base of the femoral neck;

- ascending cervical branches of the extracapsular arterial ring on the surface of the femoral neck;

- and the arteries of the round ligament.

The extracapsular arterial ring is formed posteriorly by a large branch of the medial femoral circumflex artery and anteriorly by branches of the lateral femoral circumflex artery. The superior and inferior gluteal arteries also have minor contributions to this ring.

The ascending cervical branches arise from the extracapsular arterial ring. Anteriorly, they penetrate the capsule of the hip joint at the intertrochanteric line, and posteriorly, they pass beneath the orbicular fibers of the capsule.

The ascending cervical branches pass upward under the synovial reflections and fibrous prolongations of the femoral head from its neck. These arteries are known as retinacular arteries, described initially by Weitbrecht. Any fracture of the femoral neck may lead to an injury in the retinacular arteries due to its proximity.

These ascending cervical arteries give a lot of small branches to the metaphysis of the femoral neck. Additional blood supply to the metaphysis arises from the extracapsular arterial ring and may include anastomoses with intramedullary branches of the superior nutrient artery system, branches of the ascending cervical arteries, and the sub-synovial intra-articular ring.

In the adult, there is communication through the epiphyseal scar between the metaphyseal and epiphyseal vessels when the femoral neck is intact.

The Nerves of the Trochanter

The hip joint receives multiple innervations primarily involving the hip capsule. The posterior articular nerve, a branch of the nerve to the quadratus femoris provides the most extensive nerve supply to the hip joint, including the posterior and inferior regions of the capsule and the ischio-femoral ligament.

Superiorly, the hip capsule is innervated by the superior gluteal nerve. Anterior innervation of the capsule is provided, primarily, by direct branches of the femoral nerve. However, the anteromedial and anteroinferior regions are supplied by the medial articular nerve, which arises from the anterior division of the obturator nerve.

The ligamentum teres is innervated by the posterior branch of the obturator nerve. Sensory nerve end organs and ramified free nerve endings are found in the acetabular labrum, suggesting that the labrum may provide nociceptive and proprioceptive feedback to and from the hip joint.

The Muscles of the Trochanter

The geometry of the hip allows a wide range of motion in all planes, necessitating a large number of controlling muscles arising from a wide surface area to provide good stability. The twenty-two muscles acting on the hip joint contribute to stability and provide the forces required for the movement of the hip.

The muscular anatomy of the hip region can be explained in many ways. Three groups could be defined into

- Inner hip muscles

- Outer hip muscles

- Muscles belonging to the adductor group.

Also, they can be classified as superficial and deep groups. On the other hand, they can be divided into their main actions across the hip joint.

It is joined at the level of the inguinal ligament5Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R, Ito K (2003) An in vitro investigation of the acetabular labral seal in hip joint mechanics. J Biomech 36(2): 171- 178. to form the iliopsoas. The iliopsoas is the acting horse in hip flexion, but it is also aided by the sartorius, tensor fascia, rectus femoris, and latae (TFL). Sartorius, innervated by the femoral nerve, runs from the Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS) to insert medially into the tibial tuberosity.

It plays a role in external rotation and hip abduction. Rectus femoris originates from the AIIS to be inserted into the tibial tuberosity through the patellar ligament. The gluteus maximus is considered the main hip extensor, originating from the dorsal sacral surface, posterior part of the ilium, and thoracolumbar fascia to be inserted into the gluteal tuberosity6O'Rahilly, Ronan, M.D.; Fabiola Müller, Dr. rer. nat., Stanley Carpenter, Ph.D., and Rand Swenson, D.C., M.D., Ph.D. (2004). "Etymology of Abdominal Visceral Terms". Basic Human Anatomy: A Regional Study of Human Structure. Rand Swenson, site ed. Dartmouth Medical School. and the iliotibial tract.

It receives innervation from the inferior gluteal nerve. It plays a role in external rotation, abduction, and adduction. The main hip abductors are the gluteus medius and minimus. The proximal insertion of the gluteus medius into the iliac crest is almost continuous with fascia lata.

It appears as an inverted triangle from its wide proximal base to its narrow distal insertion into the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter. The gluteus minimus lies beneath the gluteus medius. It arises from the gluteal surface of the ilium and inserts into the anterolateral aspect of the greater trochanter.

Both muscles receive innervations through the superior gluteal nerve. Tensor Fascia Lata takes its origin from the ASIS to be inserted distally into the iliotibial tract. It shares in flexion and external rotation. Piriformis muscles arises from the inner surface of the sacrum and inserts into the tip of the greater trochanter.

It plays a role in hip extension and external rotation. The external rotators (superior gemellus, obturator internus, inferior gemellus, and quadratus femoris) run horizontally below the piriformis. All play a role in hip adduction and external rotation and all receive branches from L5-S1 in the sacral plexus.

Hip adductors includes the obturator externus arising from the outer surface of the obturator membrane and inserts into the trochanteric fossa. It also contributes to external rotation and has its innervation from the obturator nerve.

The remaining muscles in this group variably have their proximal origin on the pubic bone and insert distally on the femur below the level of the lesser trochanter or in the case of gracilis into the pes anserinus medial to the tibial tubercle.

The pectineus attaches to the pectin pubis and inserts into the femur along the pectineal line and linea aspera. It also contributes to external rotation and some flexion. Adductor longus attaches medial to pectineus on the superior pubic ramus and inserts distally to the pectineus along the middle third of the linea aspera - it also contributes to hip flexion up to 70°.

Adductor brevis arises from the inferior pubic ramus and inserts proximal to the adductor longus into the proximal one-third of the linea aspera. Adductor magnus arises from the inferior pubic ramus, ischial ramus, and ischial tuberosity. It inserts distally into the medial lip of the linea aspera but also has a more tendinous insertion into the medial condyle of the femur.

It contributes also to extension and external rotation. Adductor minimus runs from the inferior pubic ramus into the medial lip of the linea aspera also contributing to external rotation. Gracilis is the only adductor that inserts distally to the knee joint.

It arises inferior to the pubic ramus below the pubis symphysis. All the adductors receive innervation from the obturator nerve. Pectineus also has a supply from the femoral while the deep aspect of the adductor magnus also has a supply from the sciatic nerve.

As previously stated, the muscles of the hip joint can contribute to movement in several different planes depending on the position of the hip, which is caused by a change in the relationship between a muscle’s line of action and the hip’s axis of rotation.

This is referred to as the “inversion of muscular action” and most commonly manifests as a muscle’s secondary function. For example, the gluteus medius and minimus act as abductors when the hip is extended and as internal rotators when the hip is flexed. The adductor longus acts as a flexor at 50° of hip flexion, but as an extensor at 70°.

In addition to providing stability and motion for the hip, muscles act to prevent undue bending stresses on the femur. When the femoral shaft undergoes a vertical load, the lateral and medial sides of the bone experience tensile and compressive stresses respectively.

To resist these potentially harmful stresses, as might occur in the case of an elderly person whose bones have become osteoporotic and susceptible to tensile stress fractures, the TFL acts as a lateral tensioning band.

Muscle weakness around the hip is usually compensated by the individual to perform the desired task of walking. An example is the Trendelenburg gait, noted by the pelvis sagging to the contralateral side secondary to weakness of the abductor muscle group on the weight-bearing side.

This is countered by the individual shifting their center of gravity towards the affected joint by leaning over. This tilting reduces the force required by the abductor.

The Physiologic Variants of the Trochanter

For the greater trochanter: The greater trochanter (and pelvis in general) may be seen as forward of the coronal line in leaning postures where weight bearing is more toward the forefoot (metatarsal heads). Usually noted in this posture will be tight hamstrings and erector spinae, weak rectus abdominis, shortened dorsiflexors of the feet, and hammer toes (as the toes attempt to ‘grip the ground’).

When the greater trochanter is posterior to the coronal line, the result is usually for weight bearing to be more calcaneal, lumbar curvature more flattened, shortened upper rectus abdominis and diaphragm, excessive kyphosis and a forward-placed head.

For the lower trochanter: Distal to the level of the lesser trochanter, branches from the femoral nerve supplying the lateral vastus muscle are crossing the ventral aspect of the femur.

An extension of the approach to or right distal to the lesser trochanter is possible from the anterior direction. The soft tissue in this area should be pushed distally. Direct anterior sharp dissection at that level should be avoided.

To reach the lateral aspect of the femur, continue the skin incision laterally, or make an additional lateral incision. The fascia lata must be split longitudinally, dorsal to the TFL along the shaft axis.

Underneath the fascia lata, the vastus lateralis muscle is exposed. The fascia of this muscle is incised dorsally, and muscle fibers are bluntly lifted from the dorsal fascia at the desired length. Perforating vessels are ligated.

The Surgical Considerations of the Trochanter

For the greater trochanter: The greater trochanter lies slightly posterior and lateral to the axis of the femur. The gluteus medius tendon attaches to the lateral border and minimus tendon anteriorly.

The piriformis tendon attaches to a fossa on the medial aspect of the greater trochanter—this is the landmark for accessing the femoral canal.

The sciatic nerve leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, below the piriformis, and traverses the thigh in the posterior aspect. Care must be taken when placing retractors behind the trochanter, to elevate the proximal femur in the wound, so that the nerve is protected.

For the lower trochanter: Distal to the level of the lesser trochanter, branches from the femoral nerve supplying the lateral vastus muscle are crossing the ventral aspect of the femur.

An extension of the approach to or right distal to the lesser trochanter is possible from the anterior direction. The soft tissue in this area should be pushed distally. Direct anterior sharp dissection at that level should be avoided.

To reach the lateral aspect of the femur, continue the skin incision laterally, or make an additional lateral incision. The fascia lata must be split longitudinally, dorsal to the TFL along the shaft axis.

Underneath the fascia lata, the vastus lateralis muscle is exposed. The fascia of this muscle is incised dorsally, and muscle fibers are bluntly lifted from the dorsal fascia at the desired length. Perforating vessels are ligated.

The Clinical Significance of the Trochanter

For the greater trochanter: The greater trochanter is not affected by the necrosis occurring within the femoral capital epiphysis and continues its growth in a normal fashion. This growth occurs by elongation at the greater trochanter epiphysis and by appositional growth at the tip and lateral side walls.

When the femoral head and neck growth lags, there is a relative overgrowth of the trochanter, the tip of which may come to lie above, and often well above, the superior surface of the femoral head.

This occurrence leads to a diminution of hip abduction and a Trendelenburg gait due to the relative laxity of the attached gluteus medius and minimus muscles.

For lower trochanter: Lesser trochanter BSIs are less common compared with femoral neck BSIs. The iliopsoas musculotendinous unit can be injured from repetitive, excessive, or unbalanced contraction while running. Injury at the tendon near the insertion can cause reactive marrow edema at the lesser trochanter, predisposing to BSI progression.

Studies have shown that BSI pathology at the lesser trochanter can proceed to compression-side femoral neck BSI. The differential diagnosis for lesser trochanter BSI includes femoral neck BSI, femoral shaft BSI, iliopsoas tendinopathy, FAI, and labral tear.

Patients with lesser trochanter marrow edema (grade 2 or greater BSI) should refrain from running or impacting activities until symptoms subside. If patients have an extension of edema into the infero-medial femoral neck, the patient should have a period of protected weight-bearing and close clinical monitoring.

Sub-trochanteric and Femoral Shaft Fracture

General Features

Best diagnostic clue:

Fracture line originating below the lesser trochanter and extending distally

Location:

Sub-trochanteric fracture: Proximal femoral shaft, within 5cm of lesser trochanter

Femoral shaft fractures can be divided into proximal, middle, and distal 1/3

Size:

Can be non-displaced or severely comminuted•

Morphology:

- High-velocity injury usually transverse or short oblique: Typically comminuted, especially in younger patients.

- Low-velocity injury usually spiral

1. Sub-trochanteric fracture:

- Usually in various alignment: Due to the pull of hip abductors on proximal fragment

- Distal fragment displaced medially: Due to the pull of adductor muscles on distal fragment

2. Femoral shaft fracture: Often severely displaced and rotated

3. Bisphosphonate fracture:

- Usually sub-trochanteric or proximal 1/3 to 1/2 of the femoral shaft

- Focal cortical thickening precedes complete fracture: Cortical thickening has a wart-like appearance.

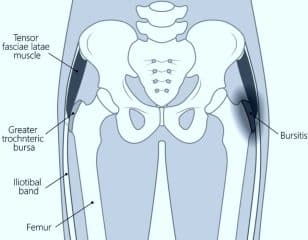

Trochanteric Bursitis

Trochanteric bursitis is inflammation of the bursa (fluid-filled sac near a joint) at the part of the hip called the greater trochanter. When this bursa becomes irritated or inflamed, it causes pain in the hip. This is a common cause of hip pain.

What causes trochanteric bursitis?

Trochanteric bursitis can result from one or more of the following events:

- Injury to the point of the hip: This can include falling onto the hip, bumping the hip into an object, or lying on one side of the body for an extended period.

- Play or work activities that cause overuse or injury to the joint areas: Such activities might include running upstairs, climbing, or standing for long periods of time.

- Incorrect posture: This condition can be caused by scoliosis, arthritis of the lumbar (lower) spine, and other spine problems.

- Stress on the soft tissues as a result of an abnormal or poorly positioned joint or bone (such as leg length differences or arthritis in a joint).

- Other diseases or conditions: These may include rheumatoid arthritis, gout, psoriasis, thyroid disease, or an unusual drug reaction. In rare cases, bursitis can result from infection.

Previous surgery around the hip or prosthetic implants in the hip. Hip bone spurs or calcium deposits in the tendons that attach to the trochanter. Bursitis is more common in women and middle-aged or elderly people. Beyond the situations mentioned above, in many cases, the cause of trochanteric bursitis is unknown.

What are the symptoms of trochanteric bursitis?

Trochanteric bursitis typically causes the following symptoms:

- Pain on the outside of the hip and thigh or in the buttock.

- Pain when lying on the affected side.

- Pain when you press in or on the outside of the hip.

- Pain that gets worse during activities such as getting up from a deep chair or getting out of a car.

- Pain with walking upstairs.

Management and treatment of trochanteric bursitis

Trochanteric bursitis is treated using treatment goals which includes reducing pain and inflammation (swelling), preserving mobility, and preventing disability and recurrence.

Treatment recommendations may include a combination of rest, splints, heat, and cold application. More advanced treatment options include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen or naproxen.

- Corticosteroid injections given by your healthcare provider. Injections work quickly to decrease the inflammation and pain.

- Physical therapy that includes range of motion exercises and splinting. This can be very beneficial.

- Surgery, when other treatments are not effective.

How do you prevent trochanteric bursitis?

Because most cases of bursitis are caused by overuse, the best treatment is prevention. It is important to avoid or modify the activities that cause the problem. Underlying conditions such as leg length differences, improper posture, or poor technique in sports or work must be corrected.

Apply these basic rules when performing activities:

- Take it slow at first and gradually build up your activity level.

- Use limited force and limited repetitions.

- Stop if unusual pain occurs.

- Some other tips to prevent trochanteric bursitis:

- Avoid repetitive activities that put stress on the hips.

- Lose weight if you need to.

- Get a properly fitting shoe insert for leg length differences.

- Maintain strength and flexibility of the hip muscles.

- Use a walking cane or crutches for a week or more when needed.

When should you seek medical advice concerning trochanteric bursitis?

Most cases of bursitis improve without any treatment over a few weeks. See your healthcare provider if you have any of the following signs or symptoms:

- You experience pain that interferes with your normal day-to-day activities or have soreness that doesn't improve despite self-care measures.

- You have a recurrence of bursitis.

- You have a fever or the area affected appears red, swollen, or warm.

In addition, see your doctor if you have other medical conditions that may increase your risk of an infection, or if you take medications that increase your risk of infection, such as corticosteroids or immunosuppressants.

The Professional Dancer’s Hip – Abductor Dysfunction

The greater trochanter is the attachment site for five muscles: the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis, obturator externus, and obturator internus. Overloading the “rotator cuff of the hip” can result in trochanteric bursitis, gluteus medius/minimus tendinopathy, and/or snapping iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome.

Hip abductor dysfunction has been shown to be more common in women compared to men, and it has been theorized that the wider female pelvis is a contributing factor. This conglomeration of diagnoses with resultant lateral hip pain7Kim YH (1987) Acetabular dysplasia and osteoarthritis developed by an eversion of the acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res 215: 289-295. has been termed “greater trochanteric pain syndrome.”

Dancers will typically present with lateral hip pain, which they report is worse with direct pressure, walking, and repetitive hip movements such as stair climbing or fan kicks.

Lumbar spine pathology may be associated with hip abductor dysfunction, and treatment for both lumbar spine pain generators and greater trochanteric pain syndrome should be considered.

Physical examination should always include side lying positioning and often reproduces the dancer's presenting pain with direct palpation over the greater trochanter, flexion-abduction-external rotation (FABER) test, positive Ober test, and weakness with pain when tested resisted hip abduction.

It is imperative to make sure the dancer is using a correct technique with resisted hip abduction to truly test the lateral musculature, as many patients will utilize tensor fascia latae and/or iliopsoas to compensate for weak hip abduction. A Trendelenburg sign or gait pattern may or may not be present and could be compensated.

Conservative treatment with physical therapy and targeted exercises will resolve most patients' symptoms by correcting muscle imbalances, particularly gluteus medius/minimus weakness.

Anti-inflammatory measures should be used with the functional goal of facilitating exercise participation and may include oral or topical anti-inflammatory medications, or an ultrasound-guided peri-tenon or bursa steroid injection.

Recalcitrant cases are rare in the high-level athlete, but may include trochanteric bursectomy, with or without Iliotibial Band release. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) may be considered for the treatment of gluteus minimus and medius tendinopathy and/or partial tears.

Rarely, surgery can be considered but should be reserved for patients with complete rupture of the tendon or chronic high-grade partial tendon tears that have failed to respond to nonoperative measures8Byrd J (2004) Gross anatomy. In: Operative Hip Arthroscopy, (2nd edn); edited by Byrd J, Springer Science, New York, USA, pp. 100-109..

Watch the following video to know more about greater trochanteric pain syndrome:

All right, guys, that is it for now for the trochanter – greater and lesser trochanter. I hope Healthsoothe answered any questions you had concerning trochanter – greater and lesser trochanter.

Feel free to contact us at contact@healthsoothe.com if you have further questions to ask or if there’s anything you want to contribute or correct to this article.

You can always check our FAQs section below to know more about trochanter – greater and lesser trochanter.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Trochanter

What Muscles Originate at the Lesser Trochanter?

The summit of the lesser trochanter is rough, and gives insertion to the tendon of the psoas major muscle and the iliacus muscle.

Which Muscles Attach to the Greater Trochanter?

The greater trochanter is the attachment site for five muscles: the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis, obturator externus, and obturator internus.

What are the Functions of the Greater and Lesser Trochanters in the Femur?

The greater trochanter gives attachment to a number of muscles (including the gluteus medius and minimus, piriformis, obturator internus and externus, and gemelli muscles), and the lesser trochanter receives the insertion of several muscles (including the psoas major and iliacus muscles).

What is the Trochanter of a Bone?

It is one of the bony prominences toward the near end of the thighbone (the femur). There are two trochanters: The greater trochanter - A powerful protrusion located at the proximal (near) and lateral (outside) part of the shaft of the femur.

Is the Trochanter Part of the Hip?

Trochanteric bursitis is inflammation of the bursa (fluid-filled sac near a joint) at the part of the hip called the greater trochanter. When this bursa becomes irritated or inflamed, it causes pain in the hip. This is a common cause of hip pain.

What's Another Name for Trochanter?

The trochanter is known to be associated with the femoris, thighbone, and femur.

What is the Best Treatment for Trochanteric Bursitis?

Is Walking Good for Trochanteric Bursitis?

Avoid High-Impact Activities. Running and jumping can make hip pain from arthritis and bursitis worse, so it's best to avoid them. Walking is a better choice, advises Humphrey.

Why Does my Trochanter Hurt When I Walk?

The most common cause of greater trochanteric pain syndrome is repeated use or overuse of the hip muscles. This can occur with frequent walking or running, suddenly increasing the amount of exercise, or standing on one leg for a long time.

Does Trochanteric Bursitis Ever go Away?

Most trochanteric bursitis resolves on its own after two weeks. If home treatment hasn't relieved your discomfort after two weeks, it's time to see a doctor. A specialist in orthopedics, rheumatology, or physical medicine and rehabilitation can help.

What Aggravates Trochanteric Bursitis?

Activities or positions that put pressure on the hip bursa, such as lying down, sitting in one position for a long time, or walking distances can irritate the bursa and cause more pain.

Which Tendon aches to the Lesser Trochanter?

Pain may be present at the insertion of the iliopsoas tendon onto the lesser trochanter, which can be palpated under the gluteal fold (with the patient in a prone position).

What Two Muscles Insert on the Lesser Trochanter of the Femur?

The psoas major and the iliacus both assist to help flex the femur (thigh) at the hip joint with insertion into the lesser trochanter of the femur. The psoas major and the iliacus are known as the iliopsoas muscle.

Why is Trochanteric Bursitis so Painful?

Trochanteric bursitis is inflammation (swelling) of the bursa (fluid-filled sac near a joint) at the outside (lateral) point of the hip known as the greater trochanter. When this bursa becomes irritated or inflamed, it causes pain in the hip. This is a common cause of hip pain.

What Happens if You Fracture Your Greater Trochanter?

The gluteus medius and gluteus minimus are abducent muscle groups with attachments located on the greater trochanter. Thus, a fracture of the greater trochanter could cause avulsion injury of these attachment points and eventually affect the abducent function of the hip joint and cause chronic pain.

Is the Trochanter Important?

The position of the greater trochanter influences the mechanical stress of the hip joint, the extent of contraction of the gluteus medius and minimus muscles, and the mechanical stress of the femoral neck. So, the trochanter is important.

Additional resources and citations

- 1Moore KL (1992) The Lower Limb. In: Clinically Oriented Anatomy, (3rd edn); edited by Moore KL, Williams and Wilkins, USA, pp. 373-495.

- 2Schuenke M, Schutle E, Schumacher U (2006) Lower Limb: Bones, ligaments and joints. In: THIEME Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System, (1st edn); edited by Ross L, Lamperti E, Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart; New York, USA, pp. 360-418.

- 3Damien P Byrne, Kevin J Mulhall, Joseph F Baker (2010) Anatomy & Biomechanics of the Hip. Open Sports Med J 4(1): 51-57.

- 4Ogden JA (1983) Development and growth of the hip. In: Management of Hip Disorders in Children, edited by Katz JE, Siffert RS (Eds.); Lippincott, Philadelphia, p. 1-32.

- 5Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R, Ito K (2003) An in vitro investigation of the acetabular labral seal in hip joint mechanics. J Biomech 36(2): 171- 178.

- 6O'Rahilly, Ronan, M.D.; Fabiola Müller, Dr. rer. nat., Stanley Carpenter, Ph.D., and Rand Swenson, D.C., M.D., Ph.D. (2004). "Etymology of Abdominal Visceral Terms". Basic Human Anatomy: A Regional Study of Human Structure. Rand Swenson, site ed. Dartmouth Medical School.

- 7Kim YH (1987) Acetabular dysplasia and osteoarthritis developed by an eversion of the acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res 215: 289-295.

- 8Byrd J (2004) Gross anatomy. In: Operative Hip Arthroscopy, (2nd edn); edited by Byrd J, Springer Science, New York, USA, pp. 100-109.